This article was originally published on November 2, 2012, during Issue 126: Only If For a Night.

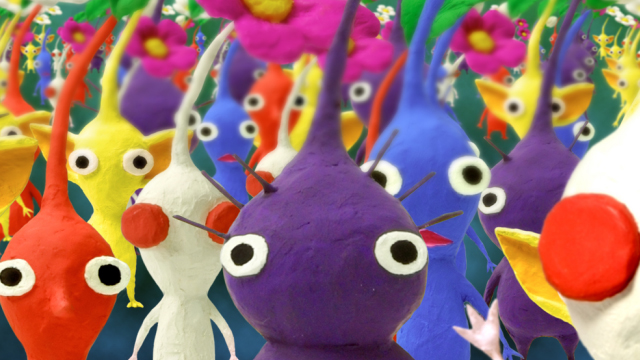

Pikmin, the brainchild of Shigeru Miyamoto, is renowned as a cute strategy game series with an equally cute cast of endearing characters. On the surface, it’s a simple story about a tiny man named Olimar, the captain of the spaceship Dolphin who employs the aid of a friendly, sentient plant race in order to return home after being stranded on an alien, but strangely familiar, planet. Scratch beneath that surface, however, and you soon discover the dark heart of Pikmin and the sociological themes that upon analysis quite deeply run through it.

Perhaps the most interesting and hidden dark heart are the parallels that can be drawn with Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness. The book focuses on Charles Marlow, a sailor journeying up the Congo river with the ostensible mission of obtaining commodities. The mission, however, soon spirals out of control when Marlow rescues a stranded westerner named Kurtz. Along the way, Marlow observes the exploitation of colonialism, and the darkness in the hearts of men, and the story culminates in the discovery that Kurtz, drunk on power and clearly taking advantage of his situation, has assumed the position and power of a man-god among the African natives and uses them to do his bidding. The natives themselves are treated as little more than background noise and are marginalised by each main character, with Kurtz using them as minions and Marlow as a threat.

Immediately, we can see the narrative of Olimar in the original Pikmin adventure follows a rather similar progression. Of course, there are some vital differences worth noting. For instance, Marlow volunteered to venture forth into the unknown, whereas Captain Olimar’s ship crash-lands and leaves him stranded on a foreign world that after 30 days he may never escape, and Olimar brings life and purpose to the Pikmin, while Marlow merely assists in changing the purpose of an existing people through the influence of another culture. Olimar’s also shown to be much more compassionate than Marlow– he’s genuinely saddened by the fate of the Pikmin, while Marlow simply regards the Africans as sub-human, remarking that a boy working an engine looks “as strange as a dog wearing trousers”. When one of his comrades is killed by a spear, he feels a slight pang of guilt but carries on without much thought for the man’s fate.

Despite these differences, though, the themes of post-colonialism are still present throughout the game. Just in case you’re not familiar with post-colonialism, this school of thought explores the damage done by colonialist efforts along with the lasting effects of a hybridized culture and the exploitation of native people. While Olimar’s use of the native population isn’t so extreme as to fundamentally alter the Pikmin’s culture going forward, it does appear to show many of the downsides of European expansion into Africa in the 1800s– particularly the disregard for the lives of natives and the large-scale export of natural resources.

The use of unpaid natives to gather natural resources and export them is characteristic of activities undertaken by white settlers in the era of the Belgian Congo, during which Heart of Darkness is set. Of particular note is the growing callousness of the characters to the death around them. In the beginning, the death of a few Pikmin in battles is treated as an emotional event, but by the end they’re so numerous that the player will easily tolerate a few dozen casualties in order to bring down a single boss.

The use of unpaid natives to gather natural resources and export them is characteristic of activities undertaken by white settlers in the era of the Belgian Congo, during which Heart of Darkness is set. Of particular note is the growing callousness of the characters to the death around them. In the beginning, the death of a few Pikmin in battles is treated as an emotional event, but by the end they’re so numerous that the player will easily tolerate a few dozen casualties in order to bring down a single boss.

Survival of the fittest is in full effect here, and one could raise the question of whether such sacrifices are necessary for the sake of one man’s ability to return home. Indeed, a central theme in both works is the sacrifice of a perceived lesser species in order to facilitate the rescue of a single man. We rightly find it abhorrent in Heart of Darkness that so many African natives should die on the whims of a few white men, but I’m sure many of us don’t even bat an eyelid when a Bulborb devours fifty Pikmin. The world of Pikmin may be rather removed from our own, hidden behind a veneer of loveable creatures and funnily-proportioned protagonists, but under the surface the premise is still the same.

In Heart of Darkness, the colonialists are the white settlers, who control the native Congolese people and oversee the natural resource supplies (the most important reason for them being in that part of the world), ruling with an iron fist without regard for the native people. In Pikmin, Olimar plays the colonialist, discovering material wealth in the form of nectar and pellets (as well as rare treasures in the second game), but in the process reveals the bloodthirsty side of the Pikmin. They owe a little more to Olimar than the Congolese owe to Marlow however, since Olimar actively helps the Pikmin develop as a species instead of exploiting their existence for his own benefit, and is largely responsible for their lives and wellbeing. Indeed, when he leaves the planet after collecting all the parts of his ship, the Pikmin will see him off, suggesting they don’t resent his presence and influence.

Yet reading Olimar’s diary entries after each day on the planet reveals his own unease about his situation as he speaks about his dwindling amount of remaining time and how the Pikmin will willingly die for him. One particularly insightful quote is:

“I wonder if these Pikmin were waiting for me to arrive. No… Not necessarily me, but an alien being like me who could fight alongside them. On this planet there are weak species, but maybe they see that they can use the power of an alien brain to climb to the top of the natural order. Such ideas make me wonder if it isn’t I who is being used by them…”

This is another key point of difference between Pikmin and Heart of Darkness— while Marlow is able to willingly leave the Congo, not necessarily with the help of the natives, Olimar must keep good faith with them in order to leave. While they do indeed need him in order to create a society capable of sustaining itself, once they have done that they could very well leave Olimar on his own. In essence, the Pikmin actually need Olimar much less than he needs them, even though the role they play is subservient.

The similarities are not universal– most importantly, Olimar seems to represent the characters of both Marlow and Kurtz rather than one or the other, both discovering the fanaticism of the natives and becoming their leader. Kurtz is a man displaying a god complex– his ability to command and control has run away with him, and he is left crazed and dying as a result. It is not clear by the end of the game whether Olimar still considers himself simply a victim of circumstance, or whether he derives some sense of importance and purpose from having acquired his own private army which may– should he become obsessed with fighting rather than recovering his ship– lead to his becoming one of the Pikmin himself.

In the characters’ use of the natives, attitudes towards another world and focus on getting home despite any costs to other people, Pikmin and Heart of Darkness share a great deal. It may sound strange at first, but a close reading reveals a great many similarities that have gone unnoticed for several years. To examine games closely strengthens the case for their recognition as an art form, and it is fascinating that perhaps the most accurate retelling of Joseph Conrad’s classic tale is not a film or play, but a story of an insignificant alien trapped on a strange world, far from home.

ShareThis

ShareThis