According to Merriam-Webster, nostalgia is the “pleasure and sadness that is caused by remembering something from the past and wishing that you could experience it again,” particularly when regarding “a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition.” In reading the reviews for DuckTales: Remastered across various video game websites and magazines, journalists overwhelmingly used the word nostalgia to describe their experience with the game and its predecessor.

“Nostalgia’s Like A Hurricane” – Colin Moriarty, IGN (the header of the article).

“Nostalgia is a wonderful thing” – Marc Camron, EGM

“Nostalgia is a funny little human trait” – Chandra Nair, Official Nintendo Magazine

“I had a similar experience as I nostalgia-dove into DuckTales: Remastered” – Robert Hathorne, PC Gamer

While reviews of Remastered weren’t uniform, swaths of journalists prefaced their evaluations by noting the role of nostalgia in coloring them. The common consensus amongst the majority of critics was that the original NES DuckTales might have impressed 24 years ago, but that time hadn’t been kind to its design. The writers then in turn went from slamming the original DuckTales to saying that Remastered didn’t live up to it, in some cases pegging the game with scores as low as a 4.5/10. Every critic is entitled to their opinion, of course, but the dismissive way that writer after writer kicked the original DuckTales to the curb rankled. Using nostalgia as the lynchpin of their arguments for why fans enjoyed the game just wasn’t reasonable. Not everyone playing DuckTales in 1989 was eight and nine years old. Like today, the demographics of 1980s gamers wasn’t limited to pre-teen boys, so it seemed unlikely that a title so many diverse people had fun playing should have such diminished capacities.

For many reading these impressions, however, the problem was the same as it had ever been: too many gaming journalists approach classic and older games with the intent to find flaws. They go into replays not to appreciate the titles for their worth as a singular experience, but to compare them to the cumulative sum of advancement and innovation that have graced the industry in the years since their release. This archaic method of evaluation has become less widespread in recent years, but the history of video games and the journalists who write about it continue to have a tumultuous relationship.

One of the worst examples of this sort of mindset came from the magazine Electronic Gaming Monthly back in 2005. EGM had compiled a list of the top ten most overrated video games. On it were titles like Ico, Banjo-Kazooie, Donkey Kong Country, and Perfect Dark, to name a few. While controversial opinions were a hallmark of EGM, this particular list was markedly bombastic. Nearly every title named was beloved by fans and had earned legacies of respect. It’s astounding to think that EGM, which was one of the leading forces in video game journalism at the time, went out of its way to find arbitrary reasons to posthumously slam those classic games. While EGM in those years had a reputation for arrogance, this list was an extreme showing of hubris. Almost every title it bombarded had, at its release, brought something new to the medium or did something particularly well for its time. EGM‘s attack was a reckless affirmation to pundits that video games were the throwaway, junk entertainment they claimed it to be. Their actions were the equivalent of film critic Leonard Maltin saying Citizen Kane sucks because new movies are all in color. (If that got your blood boiling, take solace in knowing that five years later EGM was an afterthought and Donkey Kong Country Returns was lighting up the charts).

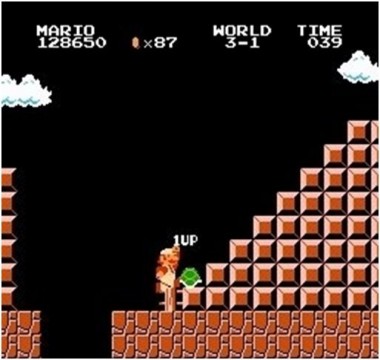

Don’t mistake this as an assertion that an old game can’t be overrated or flat out unplayable. Again, opinions are what they are, and if someone was genuinely underwhelmed replaying DuckTales they have every right to say so. Still, when looking back at the history of this incredible medium, one has to come to terms with the idea that video games are as much art as they are entertainment. Like literature, films, and television, video games have the ability to transcend the limitations of time and space. Over 200 years later, Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of Medusa hangs from the walls of the Louvre still transfixing viewers. 30 years later, The Police’s Synchronicity blares through listeners’ ear buds. The work of video game developers and designers will be and is no different. Super Mario Bros. is regularly downloaded across multiple Nintendo platforms every week, 28 years after its debut. There’s no debating that games like Super Mario World and Super Mario Galaxy have skyrocketed past the basic framework of Mario’s first outing, but that knowledge doesn’t make the title any less endearing or, most importantly, fun.

Speaking of Nintendo, the company bears the brunt of this abuse perhaps more than any other publisher or developer. Many writers make a point of questioning whether or not Nintendo’s franchises would be so popular if not for the nostalgia (there’s that word again) they spark in the minds of fans. It’s an odd allegation to make, considering critics also frequently berate Nintendo for being a company that only makes games for kids; since it’s impossible for a ten year old to be nostalgic about games that came out fifteen to twenty years ago, it would seem an unlikely motivator to get them playing. The truth of the matter is that new and old fans keep coming back to the well because the water has never turned stagnant. Nintendo’s goliath of a back catalog routinely contradicts the idea that older games are automatically supplanted by their successors, as the vast majority of its titles are arguably the equal to plenty of games released today. Critics can disrespect Nintendo all they want, but the company continues to defy expectations and remain successful. That’s not luck, but rather an intimate understanding of the industry Nintendo helped rescue.

It’s important to note that not all is doom and gloom when it comes to appreciating the past of gaming. IGN recently gave The Legend of Zelda: Wind Waker HD a 9.8 in its review, outlets like NF Magazine regularly highlight cherished bits of retro gaming glory, and Nintendojo itself embraces the old and new like no one else. In the years since EGM‘s acerbic heyday, titles like New Super Mario Bros. and LittleBigPlanet have propelled the once dormant genre of 2D platformers back into the forefront of the industry. It can’t stop there though; video games will continue to struggle with earning respect as both a form of art and entertainment so long as its most visible and vocal spokespeople remain at odds with its past. Gaming journalists have a responsibility to pick and prune where necessary, but refusing a classic game the respect it deserves by making unfair criticisms is doing everyone a disservice. It’s hard to convince naysayers that gaming is about more than mindless murder simulations when the medium’s own press actively dismiss the titles that show the breadth its capable of. The industry needs to continue preserving its past with remakes like DuckTales: Remastered, virtual distribution through services like Nintendo’s Virtual Console, and tribute systems like NeoGeo X. Here’s hoping that games like Ico never have to be smeared through the mud again.

ShareThis

ShareThis

I think about Ducktales main story of the series is a “rich eldery anthropomorphic duck taking young kids on exciting adventure” Is something that Liberal/progressive establishment wouldn’t want to catch on. So hameplay is the excuse to berate this game. If it gets a bad review, might have less players.

Um… lol?