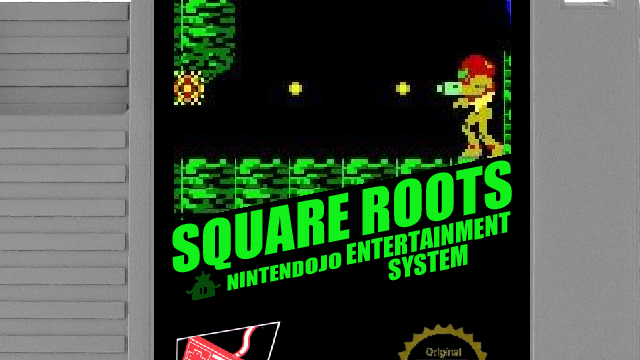

Fitting for a visit from Square Roots are those games that launched Nintendo’s various worlds and IPs. Yet inaugural titles only narrow it down so much; when I was faced with which to pick next, Metroid presented its case well. Samus’ non-eponymous adventures stood decidedly outside of the “Nintendo is for the kids” label– which, yes, had been slapped on the big N well before the current generation. As a matter of personal appeal, I’ve never owned or played any of the Metroid games, so I thought I would make Square Roots #3 a remedy to the lacuna. Plus, I really can’t say no to a side-scroller.

The 8-bit Metroid was released in 1986 in Japan, or one year after Super Mario Bros. had taken American holiday-shoppers by storm and its console, the NES, to immediate stateside success. The project was delegated to the company’s Research and Development Team 1 and led by Gunpei Yokoi (the man who, with this team, would later create the Game Boy).

Miyamoto had earned the right to pursue the Mario and Zelda franchises, while R&D1 was charged with generating new IPs. This shows in more ways than one. The music of Metroid rings darkly against the cavernous trappings of Planet Zebes. The stakes feel weightier than Mario’s pursuit of a lost princess, and truly, this was a game that could scare. The game would also shrug off the damsel-in-distress trope that Peach so willingly fell into, by revealing Samus as a woman at game’s end (if and only if players completed it fast enough– Metroid was the very first game to feature alternate endings). Even the game’s promotional material preserved this twist by referring to Samus as a “he.”

Moreover, her abilities– and vulnerabilities– are greatly opposed to Mario’s, as the developers seem to have taken special care not to step on the plumber’s feet. Mario is a brawler who jumps atop his foes, Samus a shooter working best at a distance. Mario can suffer a goomba’s sting and run straight through the thing, whereas Samus will bounce off the alien beasts of Planet Zebes, flinching. Another mechanic imparting great implications on gameplay is that Samus’ health (or energy, rather) is measured in digital increments. In Mario’s case, a simple glance at the character model (is he big? good!) tells all.

This makes Planet Zebes– the game’s one and only locale– a whole lot scarier. Incremental pieces of health must be harvested from slain enemies. Before venturing into that particularly hostile corridor, I often found myself dashing around more familiar ones, zapping enemies and collecting the energy they yielded.

The developers expected this behavior and built on it; the world of Metroid is a fully contiguous one, often more vertical than horizontal. Backtracking is a necessity, as certain areas only open once you acquire the various upgrades tucked away here and there.

In fact, Metroid quickly becomes a game of memory, one that surely many young Nintendo fans sought to relieve from their minds and map onto paper. We now have the internet for that (though looking is cheating!).

Perhaps Metroid‘s greatest victory is indeed that it managed to keep Super Mario Bros. influence at bay, despite being another side-scroller perched atop the same technology and harbored by the same publisher. The game thrives in a mature and dark stripe of science fiction that surely contemporary gamers could identify with, rather than the cheerfully odd flights of one genius’ fancy. Just as importantly, anyone looking to draw a Venn diagram comparing the two games’ mechanics won’t find much to jot down in the middle.

At 500 Wii points, Samus Aran’s maiden voyage is worthwhile for players looking to test their worth; Planet Zebes produces no shortage of frustrating moments, brain-stretching labyrinths, and dead ends. The original game’s password system still works here (you’re given one in the event of your death, upon which you explode into forgotten dust), though the Virtual Console edition matches that with an automatic save system. Revisit the game at any time to pick up where you left off.

For a well-presented history of Metroid, I must suggest Machinima’s video on the game and its successors. Among the anecdotes: the mini-boss Ridley was named after director Ridley Scott, whose landmark film, Alien, had hit theaters a few years earlier. R&D1 employees weren’t living in a bubble– even if Samus’ world, eerily, might feel like one.

ShareThis

ShareThis

Metroid is my favorite Nes game, i really liked it when i was a kid (7,8) but i never finish the game, i was so young and stupid that i didnt know what the hell where does letters that appear after i died. Now i have the game in the ambassadors program and i havent finished yet, its SO HARD!!! The athmosphere and music in this game are timeless, if you want to hear a good rwtro videogame song, just search in youtube for “Kraid’s hide” EPIC!!!!

I used to LOVE this game. Never beat it until the gameboy remake because I kept losing my passwords as a kid to continue

I still remember the justin bailey cheatcode. I know it meant baithing suit but my friends name was justin bailey so it was cool