When Warren Spector first revealed Epic Mickey in 2009, the most hotly discussed topic was the game’s surprisingly gritty aesthetic and how it looked set to be a return to the great licensed Disney games of yore. But in amongst the somewhat bristly reviews and the universal condemnation of the game’s troublesome camera, there lived an extraordinary game mechanic that was more than just a brushstroke above the ordinary.

When Warren Spector first revealed Epic Mickey in 2009, the most hotly discussed topic was the game’s surprisingly gritty aesthetic and how it looked set to be a return to the great licensed Disney games of yore. But in amongst the somewhat bristly reviews and the universal condemnation of the game’s troublesome camera, there lived an extraordinary game mechanic that was more than just a brushstroke above the ordinary.

That mechanic was how the player made their decisions.

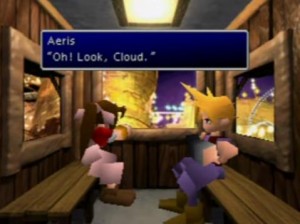

Now, I’m not saying that decision-making is something we’ve never seen before– there have been plenty of these mechanics in the past, stretching right back to the days of Chrono Trigger on SNES through to modern greats like Mass Effect. One of the first I remember really taking notice of was Final Fantasy VII‘s “Gold Saucer Date,” where Cloud goes on a romantic rendezvous with one lucky party member.

But I put to you that Epic Mickey went above and beyond what these games have done for the industry– it made players’ decisions meaningful again.

Too often we see real decisions fall into the side-quest or question-and-answer category. By “real” decisions, I mean the type of decisions that you, the player, actively make within the course of the game to change its outcome– not the ones dictated by story or circumstance, but those where you truly influence events, whether it be to obtain alternative endings or create unique scenarios within the game. To use the aforementioned Final Fantasy VII scenario, how you complete certain tasks and answer particular questions will affect which character Cloud dates and thus the dialogue they share as the scene plays out– you actively make a difference to that particular part of the story.

The turning point of Cloud’s silent, angsty affections.

But the problem with these kinds of decision-making mechanics is that they often extend no further into the overall story structure. They don’t continue to change the narrative or your character’s relationships after that single event, and are arguably exploited more for comic effect (Cloud going on a date with Barret?) than creating any real impact on the ensuing story. Even open-world games like the Grand Theft Auto series fall into this trap– no matter how long you spend jumping off skyscrapers or blowing up helicopters and essentially making your own decisions about how you choose to play, the main story is still there waiting for you to continue.

Chrono Trigger too has its flaws in this area. If we just look at the real decisions available to the player on their first play-through (therefore discarding the multiple endings for a moment), it soon becomes apparent that the other real decisions players can make are once again relatively unimportant. For the uninitiated, you’re given the opportunity to right certain wrongs and correct past mistakes once you gain the ability to freely roam the map and travel through time. Completing these tasks can alter history and thus have a lasting effect on both the world’s landscape and the lives of certain NPCs.

Once again, however, most of these real decisions are relegated to ultimately inconsequential side-quests. As much as I enjoyed the interesting insights they gave into some of the main characters, at the end of the day Lavos is still looming and you’ve still got to carry on. They’re not particularly crucial to the rest of the game. Moreover, if you make a mistake, a quick reload is all that stands in your way to rectify your errors. I for one didn’t manage to save Lucca’s mother from having her legs crushed by Taban’s machine. When I failed, I seriously considered hitting the power button and re-starting the scenario to do it right.

But then I stopped and reflected. I had made a choice– in real life you often don’t get second chances if you mess up, so why should this be any different? It was my own fault I didn’t poke around Lucca’s house a bit more to find the password which would have stopped the machine in time, so I decided to see the consequences of my actions through and carry on with the game (it also didn’t help that I hadn’t saved for a while, but that’s beside the point).

Sorry, Lucca. My bad.

Of course, a second (and third, and fourth, and fifth, and ad infinitum) play-through of Chrono Trigger allows players to make some of the strongest and perhaps most meaningful real decisions games have ever afforded– want to defeat Lavos right at the beginning of the game? No problem. Want to miss out a bunch of characters and plot points? Sure. Want to play it all the way through again? Why not.

But Epic Mickey did things differently. Epic Mickey combined these two popular methods of decision making (questions and side-quests) and built them directly into its evolving narrative on the first play-through. Even more importantly, it prevented players from going back and changing their decisions by implementing an auto-save feature. I’m not saying it’s perfect– it still stumbles into the pitfall of a too easily defined good vs evil dichotomy– but I believe that more games should follow in its footsteps.

One of the greatest merits of Epic Mickey‘s cause and effect system was how the consequences of the player’s decisions didn’t materialise right away. While players were often presented with an immediate sense of whether a choice was right or wrong, the results of those decisions lay hidden under the surface.

There are a hell of a lot of Petes in this game, and all of them force players to make fundamental decisions which will affect their future progress.

For example, early on in the game you meet Small Pete. Now Small Pete is in a pickle– he needs you to find an item for him to prove he’s innocent of crashing his boat into Gremlin Village. The choice itself is a simple one– if you decide to give Small Pete’s logbook back to him then the Gremlins are appeased and all is well; but if you decide you’d rather exchange the logbook for a one-time-only collectible pin from Shaky the Gremlin instead, then Small Pete is rather stuck.

For a while I erred on the side of Shaky’s collectible pin. After all, this is a character I won’t meet ever again, right? What possible harm could I do by ignoring him and getting that shiny pin in my collection? He’s Pete– he’s meant to be Mickey’s arch rival. Why should I help him?

Despite the temptation though, my moral compass eventually won out and I returned the logbook to Small Pete, expecting a shower of thanks and praise for my good deed. To my dismay though, he didn’t give me anything at all for my efforts and all my years of expecting immediate and tangible rewards for completing in-game tasks suddenly came crashing down on my head. Needless to say, I felt extremely hard done by.

The thing was, the game had rewarded me– I just didn’t know it yet.

And it’s here where Epic Mickey really shines. Had the auto-save feature not prevented me from going back and manipulating the outcome of the scenario, I may well have changed my decision to seek the instant gratification I so desired. But with my decisions set in stone, I could do nothing but see my choices through, and it turned out that because I had helped Small Pete, I was also given a different one-time-only pin from Big Bad Pete when I arrived in Mean Street, as well as a bunch of e-tickets and treasure as a thank-you present. If I hadn’t helped him, I would have not only missed out on Big Bad Pete’s pin, but also an item I needed to progress (though it was also available through other means), and I would have been told menacingly to “watch my back.”

And it’s here where Epic Mickey really shines. Had the auto-save feature not prevented me from going back and manipulating the outcome of the scenario, I may well have changed my decision to seek the instant gratification I so desired. But with my decisions set in stone, I could do nothing but see my choices through, and it turned out that because I had helped Small Pete, I was also given a different one-time-only pin from Big Bad Pete when I arrived in Mean Street, as well as a bunch of e-tickets and treasure as a thank-you present. If I hadn’t helped him, I would have not only missed out on Big Bad Pete’s pin, but also an item I needed to progress (though it was also available through other means), and I would have been told menacingly to “watch my back.”

It’s this state of unchangeable and temporary ignorance that I find so refreshing in Epic Mickey. Had I known about Big Bad Pete’s reward, it would have significantly altered how I approached the problem, reducing the meaning of my decision to nothing more than “do I want to get this pin or that pin?”. It would have stripped away all other moral dilemma or nuance of character development to trivial individual gain, and ultimately I don’t think that’s particularly satisfying in the long run.

Aside from Epic Mickey, the only game I’ve ever felt truly one-upped by is Chrono Trigger‘s infamous courtroom scene, which is perhaps the most devious slap in the face to RPG fans the world over. A whole series of actions and decisions I’d made were completely derailed in front of me and I’ve never felt so little in control– but it was also one of the game’s most exhilarating and exciting moments.

All in all, it’s so common to know exactly how your actions will play out and thus micro-manage those consequences to your advantage that I think we’ve lost the ability to be genuinely surprised any more by how a game’s events might develop. There’s no challenge or meaning in knowing how everything will react around you, and it’s my hope that there will be more games in the future like Epic Mickey which will change and bend with the player’s decisions and adapt to their responses. As I said earlier, Epic Mickey is by no means perfect, but it’s surprising what a small addition like an auto-save feature can have on this long-established game mechanic.

ShareThis

ShareThis