|

By 1985, the video game market in the United States was at an all-time low. Console manufacturers had glutted the market with so many different systems, that the entire industry collapsed on itself from the sheer weight of its girth. The me-too mindset at the zenith of the Atari-era of the industry had spiraled out of control, to the point that even retailers like Montgomery Wards and Radio Shack had thrown their hats into the ring with their own systems for sale. Consumers had become so bombarded with redundant and confusing console offerings that, coupled with a dip in software quality, they began to reject video games in droves. When Nintendo finally arrived on Western shores with its Nintendo Entertainment System in tow, the company was met with skepticism and more than a little derision. Flash forward 29 years later and 61.9 million units sold, however, and one finds that the NES single-handedly revitalized the video game industry and remodeled it into the medium that fans know and love today. Not bad for an upstart card and toy manufacturer!

To understand where NES came from, it’s necessary to go back a ways to 1889 and the origin of Nintendo in Japan. Fusajiro Yamauchi was the company’s founder, and he had big dreams of manufacturing Hanafuda playing cards. Hanafuda, essentially the Japanese alternative to Western-style gambling card games, was very popular, and Yamauchi believed that by producing intricate and beautiful cards, Nintendo would be able to differentiate itself from the cookie-cutter offerings of his competitors. He was right. Nintendo thrived as a card manufacturer, which sustained the company up until the 1940s. Nintendo had remained within the Yamauchi family for three generations, with its third president, Hiroshi Yamauchi, taking the reigns in 1941. Though entitled to the position by birthright, Yamauchi was thrust into the role against his wishes. As such, he took to the job with a great deal of aggression and ambition.

Yamauchi, who had labored exhaustively to distance himself from Nintendo, only stepped in to fulfill his duties at the behest of his dying grandfather. Feeling he had no choice but to acquiesce, Yamauchi was ultimately swayed, but with the caveat that the business would be run his way, and nobody else’s. Nintendo was rearranged internally to suit his needs, and any objectionable personnel were remorselessly ejected. From the outside, Yamauchi’s actions might have been perceived as petulant, but there was more to these changes than pure rebelliousness. The new president knew that if Nintendo was going to survive, it needed to change. Hanafuda cards were still selling, but the world was evolving, and Yamauchi wanted to position Nintendo to take advantage of these shifts.

It was a prescient view, but Yamauchi didn’t totally know what he was doing. Nintendo took on a number of different initiatives to try and diversify its offerings, including love hotels and instant rice, to name a few. While bold, they all eventually petered out to little success. Things were looking uncertain, until 1966 when Yamauchi met an inventive nobody toiling away in the bowels of one of Nintendo’s manufacturing plants. That nobody’s name was Gunpei Yokoi, a simple maintenance worker who had been hired by the company the previous year. In an effort to entertain himself during long days of work, Yokoi had crafted a simple extending arm that could snag objects a short distance away. Yamauchi took a fancy to the device, finding it irresistibly clever and, more importantly, potentially marketable. An eventful conversation later, Yamauchi ordered Yokoi to design the device as a toy for mass production. The end result was the Ultra Hand, which became a huge hit in Japan. Yamauchi had found Nintendo’s new muse, and it was toys.

As a toy maker, Nintendo did quite well for itself, pumping out popular diversions such as the Ultra Scope, Ultra Machine, and even a device called the Love Tester. Still, despite the success, Yamauchi was becoming more and more cognizant of the growing market of electronic games. His company had made strides with a beam gun game that had found an audience in arcades, but it only served to scratch the itch in the back of Yamauchi’s mind. By 1975, Nintendo had licensed the Magnavox Odyssey for sale in Japan, which served as the tipping point for propelling the company into the world of video games. As luck would have it, Yamauchi wasn’t alone with his vision, as his righthand man Yokoi was thinking along the same lines. An eventful trip on a subway train had left Yokoi with an idea for a portable video game device that would go on to become something called Game & Watch.

The legend is that Yokoi had seen a businessman fiddling with a pocket calculator to amuse himself during his commute. The sight of the man made Yokoi think that a game system roughly the size of a calculator, powered by the same cheap, versatile LCD technology, could be wildly successful. When the first unit sold in 1985, the designer’s intuitions were proven correct, as Game & Watch became a hit and spawned an entire line of handhelds with different games and styles that cemented Nintendo as a video game maker. Part of the line’s allure came from its budget-friendly cost and generous battery life, not to mention how portable the things were. The philosophies of Yokoi, which included the notion of using old technology in creative ways, became the mantra of Nintendo (indeed, even to this very day). The ball was rolling, but Yamauchi believed Nintendo could do more. As fate would have it, Yamauchi had already hired the very man to push that ball straight up the side of a mountain back in 1977; his name was Shigeru Miyomoto.

Nintendo had already put out a small smattering of arcade games that were seeing limited playtime in Japanese arcades. Miyomoto was a young designer who had recently contributed to the design of a title called Radar Scope, which was doing well at home, but struggling greatly in the US. As a result, an entire warehouse full of the arcade cabinets were gathering dust, and Yamauchi was struck with an idea; redesign them. Rather than scrap the units for a loss, the Nintendo president instead tasked Miyomoto and Yokoi with taking the Radar Scope rigs and turning them into something new. What started as a Popeye game eventually transitioned into what we all know and love as Donkey Kong. Despite skepticism from Nintendo’s localization team, the game became a roaring success, due in part to how it went against the grain of the popular space shooter and maze games of the time. Donkey Kong was followed by a handful of sequels and another, quirky title; Mario Bros. Mario, who was Jumpman in DK, was bumped up to leading man for the new game, which took cues from Midway’s Joust. It, too, became popular, and suddenly Yamauchi found his company ready to make the next leap to home console manufacturer.

Yamauchi set his developers to work creating what would be dubbed the Family Computer (or Famicom, as its more commonly shortened to). The system was a marked leap above the consoles that had come before. Its controller was the most notable change, with an intuitive d-pad that povided a level of control that was unheard of, up to that point. The d-pad itself was, fittingly, an invention of Yokoi’s that had graced some of his Game & Watch titles; old tech, new use. It was an ingenious adaptation for Famicom, as it resolved a number of input problems that older systems like the Atari 2600 and ColecoVision were plagued by. Joined with its solid A and B buttons, the controller was ready to handle the most demanding of video games. The system was no slouch graphically, either, despite its 8-bit processor being slightly behind the times. The argument for scaling the graphics back a bit was that it would allow Nintendo to keep the system economical for both production and consumers, and was still capable of producing better-looking games than what was already on the market. Like so many of his decisions up to that point, Yamauchi agreed with the rationalization and was validated by incredible sales.

What was a hit in Japan, however, was not a guarantee in the West. Still shaking from the gaming apocalypse of recent years, no one was very enthusiastic about trying to sell Nintendo’s Famicom. The company, outside of Donkey Kong and Mario Bros., was a veritable unknown to American gamers, and retailers were treating anything associated with video games like nuclear waste. Console manufacturers were approached, with Atari being the one that came closest to making a deal. However, after a bit of a mixup over what Atari perceived to be underhanded dealings with Coleco (who in turn had pirated a copy of Donkey Kong to run on its hardware and showed it off without permission), the company backed out in the eleventh hour. Yamauchi was irked, but he believed in Famicom and knew that Nintendo was offering something different, something that American players would embrace. No longer willing to wait on others, Yamauchi decided that Nintendo itself would handle the duties of marketing and selling the Famicom in the US.

The Western market was a different beast than Japan, though, and Famicom wasn’t quite what it needed to be to see acceptance there. Physically, Famicom was completely overhauled for the West. Gone were Famicom’s red and gold hues and hardwired controllers, replaced with cool gray and black, and controllers that could be plugged and unplugged. The name was the other thing to go. Famicom elicited visions of computers in English, which was misleading. Further complicating matters, retailer apprehension to sell video games also meant that the console couldn’t be marketed as something that, well, played video games. As a result, Nintendo settled on calling it the Nintendo Entertainment System and played up a peripheral device called R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy) to push the console as more of a toy than video game system. The ploy worked, and NES arrived on store shelves in 1985, along with a little game called Super Mario Bros.

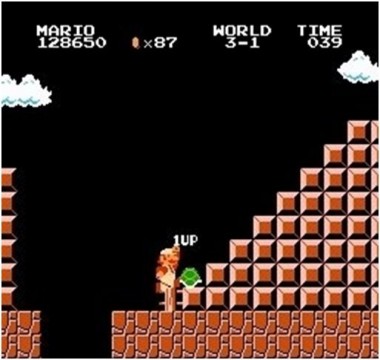

A pseudo-followup to Mario Bros., Super Mario Bros. would prove to be something beyond a simple launch title. SMB didn’t just wow players, it floored them. Entirely new gameplay and control concepts were introduced to players the first time they sat down and played the game, completely obliterating common conceptions of what a video game should be. Miyamoto, the designer behind SMB, stuffed his creation with so much spirit, ingenuity, and fun, that it landed him in history books as one of the most brilliant video game creators in history. For the people of 1985, though, SMB was simply one of the most effective system sellers anyone had ever seen. NES became a phenomenon, as it reinvigorated the industry and established Nintendo as the premier video game software and console maker in the world. R.O.B. might have gotten Nintendo a seat at the table, but SMB quickly swapped the company’s chair for a throne.

It’s impossible to overemphasize how critical NES and Super Mario Bros. were to the continued growth of the video game industry. Dozens of series that are still played today, including Mega Man, Castlevania, Ninja Gaiden, Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and more, were born on the system, and in turn served to inspire generations of today’s leading game designers and creators. Like the adoption of linear perspective in art, the introduction of NES into the landscape of video games propagated further innovations and inventions, many of which continue to come from Nintendo itself. What started as a simple need by Yamauchi to step out of the shadow of his family’s legacy, culminated in the recreation of an entire industry of entertainment and art. Anyone who enjoys playing video games today owes a debt of gratitude to Yamauchi, Yokoi, and Miyomoto for their incredible contributions.

ShareThis

ShareThis