I’m not one of these people who tends to finish games soon after release. Or quickly. Or sometimes ever. (Sorry, Kingdom Hearts 2.) While everyone else most likely breezed through Super Mario Galaxy 2 within a month of its release, I’m still trudging away, trying to collect all the stars. This genuinely occurs because when I start a game, I get stuck after a while and completely lose interest. The time between losing interest and regaining said interest can vary, sometimes a few weeks and sometimes it’s several months. With Pikmin, it was seven years.

Because when I was ten, Pikmin was pretty hard. And when a Bulborb came charging at me, I squealed and shut off the console. It was a brief affair between a misunderstood game of sheer imagination and magnificence and a little kid who would have been quite happy just playing Pokémon Gold until the battery in the cartridge had died. Luckily, I returned to the game last Easter and positively romped through it, collecting every single ship part and falling in love with the adorable and loyal Pikmin creatures in the process.

More than that, Pikmin inspired and intrigued me. Thanks to the somewhat dizzying delay in my playing of the game, I had began to study cellular biology by the time I got round to visiting The Distant Planet. As I saw Captain Olimar speed away from that definitively alien world, the only question that struck me was, “Could Pikmin be possible?”

Using both my vague knowledge of biology (though hell, I got an A) and my evil genius-esque desire to create new forms of imaginary life (which I think I successfully achieved in the Pokémon franchise), I decided to figure out whether Pikmin could evolve in the future or if they already exist somewhere today.

What Olimar points out very early after crash landing on The Distant Planet is that Pikmin are a species that can only be defined as a plant/animal hybrid. Essentially this makes Pikmin a creature that is predominantly fauna (animal) but with some significant flora (plant) attributes. Pikmin can be seen as more animal than plant because they can walk or run to escape danger or gather resources, while a plant has to remain static and instead uses leaves and roots to gather nutrients and sunlight to produce food. (This was a lesson in Biology; I’m not just making it up as I go along. Honest.)

The opposite of Pikmin, i.e. a plant with some minor animal aspects, can be found in our world in the forms of Pitcher Plants or Venus Fly Traps, as these plants catch prey which is digested to collect necessary nutrients as opposed to the majority of plants which collect nutrients found in moisture from the soil.

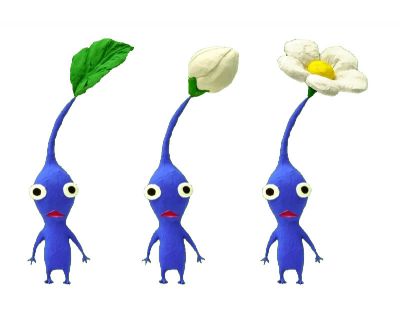

Olimar never sees the Pikmin actually eating anything, so it can be assumed that the leaf, bud or flower atop a Pikmin’s head is the primary source of energy for the creature. In normal plants, a green pigment called chlorophyll found in leaves absorbs the energy from sunlight and uses it in the process of photosynthesis to make food reserves, such as glucose or starch, which are then broken down by the plant during respiration to create raw energy for the plant to be able to do everything it needs to function.

Animals have evolved past the need for photosynthesis because they gain sugars to break down in respiration from their food intake. Every time you eat something, it gets broken down in your stomach into simple sugars like glucose before it goes through the rather long-winded process of respiration that, in turn, produces energy that is stored in molecules of Adenosine Tri-Phosphate, known as ATP. This energy is released when required and is involved in everything from cell division to fighting off viruses to sex cell production. (No giggling!)

But I digress. Pikmin are animal creatures that still gather energy by the processes used by plants. The leaf atop the Pikmin’s head collects energy from sunlight through various pigments to make food to break down again in order to function. (Technically adult, flower Pikmin should have a leaf too but we can assume that these were removed for a more simplistic design.) While this sounds completely maddening to most people– an animal that gathers food like a plant– a real life example of Pikmin actually exists. It was my recollection of this creature that inspired me to research Pikmin’s feasibility.

Before you wonder why you’ve never seen an animal like this before, it’s a creature only visible through the use of a microscope, which are actually rather fiddly but still are pretty cool. (Source)

This is a creature called Euglena (pronounced U-glean-a). Apologies for anyone who was expecting a dog that resembled Bulbasaur, but this is real life here– it was the best I could do. Euglena are single cell organisms, like amoebas, but instead of consuming raw materials like nearly all other animal cells, it instead produces food via photosynthesis. The key giveaway to this is that a Euglena cell (such as the one above) is bright green, much like a healthy plant, and this is because of the chlorophyll present in the cell which is responsible for absorbing sunlight and converting it into a usable energy.

And while you might think that Euglena is a plant (it does photosynthesize after all), a Euglena cell lacks the defining feature of a plant cell: the cell wall. While all cells have a membrane (made up of proteins and phospholipids that form a “fluid mosaic boundary” if you want to get technical) that goes around the perimeter of the cell, plant cells have an additional barrier around them called the cell wall. Unlike the membrane, this wall, which is made up of dead cellulose fibers, is rigid and cannot change shape, giving the plant cell a stable shape. All plant cells have a cell wall and it is often referred to as “the defining feature of a plant cell.”

But Euglena doesn’t have a cell wall. Like all other animal cells it only has a membrane, allowing it to change its shape as and when required. This allows Euglena cells to gain energy in the conventional manner used by single cell organisms; moving around their prey and enveloping, consuming and digesting them once inside the cell.

Also adding weight to the argument that Euglena are in fact animal cells is the fact that they are able to traverse their watery environment using their “flagellum” tail. As discussed before, moving towards (or away) from a stimulus is the typical animal response (deriving from the Darwinian “fight or flight” theory), whereas plants are somewhat rooted in place, if you’ll pardon the pun. Furthermore, “flagellum” is the best word, ever. Just say it out loud… “fla-gel-ummm.” It’s guaranteed to put a smile on your face.

So Euglena and Pikmin both have a lot in common, if you discount appearances at least. Both function through the aid of photosynthesis, instead of digesting food as their primary source of energy. Both also show the key components of animals, the act of movement of their entire structure towards resources and a lack of cell wall. Remember how Pikmin can often stretch when attacking enemies? I bet they couldn’t do that with a nasty old casing of cellulose around them, could they? (They wouldn’t be able to walk, either, but never mind that.)

Euglena are both the nearest living cousins to Pikmin and also possibly the first step in their potential evolution. As unlikely and far-fetched as it may seem, it’s fascinating to see how modern-day fictional creatures have equals in the natural world, just as mythical creatures such as dragons and unicorns have in the past. And while we aren’t likely to see it in our lifetime (or any of our next twenty generations’ descendants), there may be a day when life such as Pikmin is discovered, whether it is on our planet or another in some distant galaxy. The potential is there; Euglena holds the potential for everything that Pikmin represent. Real life may just be a few million years behind schedule.

ShareThis

ShareThis