Majora’s Mask is notable in gaming circles not only because it is the direct sequel to Ocarina of Time, but because it is so utterly different from the rest of the games in its series. The title forgoes all of the conventions associated with its franchise– including its own mythology– and instead creates a new world to serve as its setting. The plot certainly stakes bold and unfamiliar territory for the series, but that does not mean it is altogether original; in truth, the game follows one of the oldest narrative archetypes in existence, its roots stretching as far back as Sumerian mythology, particularly the story of Inanna (the goddess of fertility and war) and her descent to the underworld.

The reasons for Inanna’s descent are never fully explained within the source poem (she claims it is to attend her brother-in-law’s funeral rites, but the gatekeepers of the underworld do not believe her), but the story begins with her already making preparations for the journey. She adorns herself with jewelry and other elaborate garments, which come to represent her divine powers and act as a protective measure lest something goes awry during her descent (as no one who enters the underworld has ever been able to escape). As an added precaution, she tells her servant Ninshubur to appeal to the gods Enlil, Nanna, and Enki for assistance should she not return within three days.

As she begins her journey, she is stopped by the first gatekeeper of the underworld and is asked to remove one of her garments. She questions why, but the gatekeeper says it is merely customary, and she obliges. At each of the seven gates she encounters, she is asked to remove a garment until she finally arrives at her elder sister Ereshkigal’s throne, naked and powerless. Despite this, she orders Ereshkigal to rise from the throne and sits on it in her place, which angers both her sister and the Anna, the seven judges of the underworld. As punishment, she is transformed into a corpse and placed upon a hook.

Three days pass and Inanna still has not returned. Ninshubur does as her mistress wished and pleads with the gods for help. Enlil and Nanna refuse, but Enki offers his assistance and creates two divine beings from the dirt under his fingernails to travel to the underworld and appease Ereshkigal. They do as he instructs, but when they arrive at Ereshkigal’s throne, they find her in great pain. She offers them anything they wish if they could relieve her, but they only take Inanna’s corpse and leave.

On their return to the land of the living, they are followed by Ereshkigal’s demons who seek someone to take Inanna’s place. They scout many potential replacements, but deem each one unsuitable for various reasons. Inanna, reanimated, offers her husband Dumuzi, but his sister intercedes and offers to go in his stead. A compromise is settled, and it is decided the two shall alternate every six months. Interestingly, the tale ends with a line of praise for Ereshkigal, though its context is indiscernible as the last portion of the work is fragmented.

While the myth has, admittedly, been severely glossed over for the sake of brevity, the parallels between it and Majora’s Mask should still be immediately apparent: Link, before he is able to set foot in Termina, is stripped of his ocarina, horse and, in essence, his sword, much in the same way as Inanna is stripped of all her protective garments before she arrives at the underworld. Likewise, Link’s transformation into a Deku Scrub at the hands of Skull Kid directly mirrors Inanna’s transformation into a corpse by Ereshkigal. Both characters are rendered powerless before their respective antagonists, and each must appeal to other gods (Inanna to Enlil, Nanna, and Enki; Link to the Goddess of Time) for salvation from their state. Even the three-day motif is present in both stories, further strengthening the link between the two.

The similarities run deeper than just these examples. While it may seem like the connection between the stories is strongest with regards to Link’s character arc, he is not the only one to find a parallel in the archetype– Skull Kid, too, has a mythological antecedent, fulfilling the role first established by Ereshkigal. The two share a number of commonalities: both have a preexisting relationship with the protagonist of their respective tales, and both have been, to one degree or another, spurned by their isolation (Ereshkigal by her separation from the other gods; Skull Kid by his from the Four Giants). Both characters are also redeemed to the audience by the end of each tale– in the Inanna myth, Ereshkigal is praised, while in Majora’s Mask, Skull Kid, free from the malevolent grasp of the eponymous relic, is returned to his normal, innocent self. This last point in particular is important because it signifies that neither character was truly evil in their intentions, making each much more sympathetic.

Skull Kid’s full significance, however, cannot be completely understood until we take a look at mythologist Joseph Campbell’s interpretation of the Inanna story. In his most famous work The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell deconstructs the prostration of Inanna before Ereshkigal and comes up with the following analysis of the scene: “The hero…discovers and assimilates his opposite (his own unsuspecting self) either by swallowing it or by being swallowed. One by one the resistances are broken. He must put aside his pride, his virtue, beauty, and life, and bow or submit to the absolutely intolerable. Then he finds that he and his opposite are not of differing species, but one flesh.”

Like Inanna and Ereshkigal, the bond between Link and Skull Kid is a thematic one: both characters, at the start of the tale, have recently parted with their dearest companions, and the game at least in part serves as a chronicle of the ways in which these two deal with this same event. In order for these two opposing sides to be reconciled, they must be pitted against one another; thus Link, in his quest to reunite with his lost friend, encounters his thematic foil in Skull Kid, who represents the darker side of loss and loneliness. The hero-villain relationship the game establishes between these two characters is simultaneously strengthened and blurred by their similar motivations, ultimately depicting the pair as two sides of the same proverbial coin. The game then, much like the myth as interpreted by Campbell, becomes a journey of self-discovery, one in which Link and Skull Kid are not antagonists but two facets of the same character.

Majora’s Mask is not the only tale to build upon the foundation laid down by the Inanna myth; there is another well-known story that is just as firmly entrenched in the archetype, one with which the game shares perhaps even greater similarities.

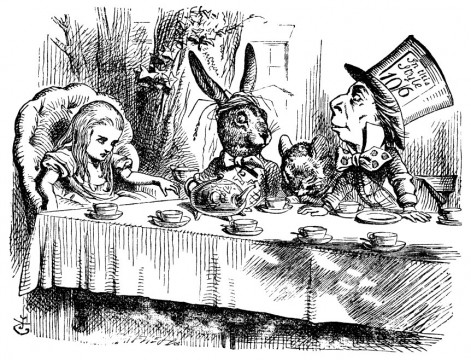

While the plots of the two works may differ wildly, it is easy to see how Alice in Wonderland assimilates the Inanna archetype into its own mythos: Alice herself unwittingly descends to the “underworld” of Wonderland, where she undergoes various transformations and is antagonized by many of the land’s inhabitants. The themes of the myth have been largely eschewed for its own idiosyncratic set of ideas and symbols, but the book still relies heavily upon the narrative structure first pioneered by the poem, so much so that the “rabbit hole” has become one of its defining and most recognizable features. Where Inanna established the descent as a storytelling device, Alice popularized it, to the point that its influence can be felt in countless other works of fantasy, Majora’s Mask included.

This comparison may seem like an inappropriate one as Majora’s Mask does not teeter on the brink of utter insanity quite like Alice in Wonderland does, but there is still some merit to it. Termina is certainly a strange place when compared to Hyrule, not only in its geography but also in the characters who inhabit it, and this is demonstrated at every corner of the game: the overgrown mushrooms of Woodfall, the man who lives in the toilet, talking monkeys, even the face in the moon all add up to an experience that is beyond fantastical and is more surreal. What perhaps contributes most to this feeling is the fact that none of the land’s aforementioned features (including the face in the moon) seem strange to any of its inhabitants, leaving only Link (and, by extension, the player) to find the slightest discrepancy in normality unsettling. Of course, every Zelda title has its share of strange quirks, but none so as abundantly as Majora’s Mask. This is not even mentioning Tingle, who is perhaps the strangest character in any Zelda game to date. His dress and demeanor call to mind the outlandishly zany characters that populate Alice in Wonderland, and his very presence adds another layer of surreality to the game and its world.

Despite both being based upon the same mythological archetype, Majora’s Mask begins more like Alice than it does the Inanna story: where Inanna ventured to the underworld of her own accord, Link, like Alice, happens upon it by accident while giving chase to another character. Both of these stories also place a great emphasis on the strangeness of their setting, so much so they almost become characters in and of themselves. This contrasts starkly with the Inanna myth as it does not describe the underworld in any sort of detail, focusing instead on the characters and themes of its story. Such an approach would not be possible in either Majora’s Mask or Alice in Wonderland as the setting in each work is inextricably tied to the themes it portrays. It is for these reasons that Majora’s Mask can be seen as a retelling of the Inanna myth as distilled through the lens of Alice in Wonderland, combining the themes and narrative structure of each to create an interactive experience wholly its own.

Whether or not Carroll and Aonuma were even aware of the Inanna myth, let alone intended to forge their respective works in its mold, is, of course, subject to speculation, but that these two radically different tales share a common foundation clearly illustrates the influence and reach of mythology in the various narrative mediums. Indeed, that both of these examples mirror the Sumerian myth so closely demonstrates not only the inseparability of mythology from storytelling, but also the persistent significance of the source tale. Myths endure because they contain some underlying insight into the human condition, and this especially holds true for the Inanna story in all of its aforementioned incarnations. How appropriate it is that, in an attempt to differentiate the game from its predecessor, Nintendo crafted a title that is based upon– and is itself– a symbolic journey of self-discovery.

ShareThis

ShareThis

I’ll always have fond memories for TLOZ: MM. While I can’t say it’s my all-time favorite, it is definitely one-of-a-kind and worth playing several times over.

Too bad they never followed up with a new Zelda game regarding what happened to Navi. Whey did she just leave and why is Link looking for her.

yeah I always had the feeling that the “looking for Navi” part of the plot was abandoned all too quickly…