As gaming continues to mature as an artistic medium, more attention will be paid to the various individual parts that comprise it. Narrative in particular is fast becoming one of its most vital elements, and an increasing number of titles– indie and blockbuster alike– are placing a greater emphasis on the tales they weave. This is certainly an exciting prospect for the industry as a whole, but the unforeseen danger of this development is that far too many designers are approaching it from the wrong perspective. Simply grafting a linear plot onto the games they create (or worse, building the game around a linear tale) often counters some of gaming’s strengths, specifically interactivity and the freedom to explore virtual spaces.

Three-dimensional games in particular strive to achieve an open-endedness that was not possible when the industry was still in its infancy, but by and large the process of storytelling has not evolved alongside this progress in technology and game design. As a result, while many titles offer the player an expansive world to explore as he or she sees fit, this element of the game is often separate from its narrative, unaffected by (and itself inconsequential to) the story. There may seem like nothing substantially wrong with this approach, but because it fails (or, at the very least, makes no effort) to marry narrative with the underlying game design, the title feels more like a video game rather than an immersive experience, falling well short of the artistic heights the medium can achieve.

Metroid Prime remedies this problem by eschewing narrative (at least in the traditional sense) almost completely: rather than establishing the plot at the game’s outset, you are instead given a brief mission synopsis from which the story organically unfolds. When you touch down on the derelict frigate orbiting the planet of Tallon IV, you are merely told to investigate the vessel because it had been broadcasting a distress signal. After that little bit of exposition, the environment itself takes up the story’s reins through its design, and you can easily glean from the bodies strewn about the ship’s fiery wreckage that a sudden and unexpected battle had occurred not long before your arrival. The game’s chief storytelling mechanic, the ability to scan objects of interest with your visor, further fleshes out this scenario with detailed information on all of the victims (including comprehensive accounts of the injuries they had sustained) and the surrounding rubble, gradually filling in all of the blanks in the plot until you come upon the creature responsible for the disaster. After doing battle with the monster, you unwittingly trigger a self-destruct sequence and must retreat to your own ship as quickly as possible, but before you are able to you encounter your archnemesis, Ridley, recently awoken from a cybernetic stasis. He flees the frigate, and without a word your next objective becomes clear: track down the space dragon and defeat him. Samus follows him to the nearby planet, and the game proper begins.

After this gripping introduction, the narrative recedes beneath the surface of your more immediate objectives, but it never disappears entirely: it serves as the underlying motive behind all of Samus’s actions on Tallon IV, and it rears its head each time you scan a piece of lore or infiltrate one of the many Space Pirate facilities that litter the landscape. Indeed, that the title is able to maintain the player’s interest in the proceedings with very few cutscenes (and absolutely no character interaction) is testament to this minimalistic method of storytelling, and it proves that a less-is-more approach can be tastefully employed without sacrificing any depth to a game’s narrative.

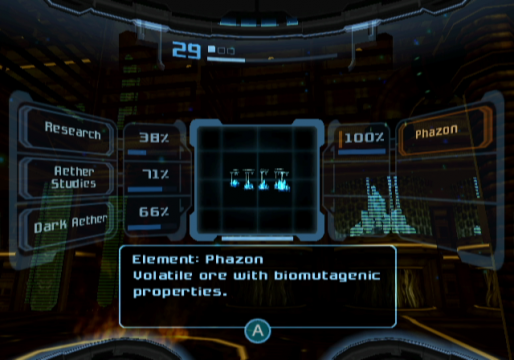

Beyond being a means of unobtrusively continuing the story, scanning also offers players a tangible reward for their exploration, further strengthening the symbiotic relationship between narrative and gameplay. Each room in any of the game’s environments is distinct in its design and purpose, and those who deviate from the “main path” out of curiosity will stumble upon a fragment of Chozo lore or a Space Pirate log entry for their efforts. These are indirectly linked to the title’s larger narrative, but their greater purpose is to more fully develop the Metroid mythos, giving Tallon IV a detailed back story that makes it feel almost like a character in itself rather than merely a backdrop for the game’s plot. The title can certainly be played without ever noting any of these additional pieces of information, but the planet and the objectives lain before you take on an entirely different color when you read the final scrawlings of a Chozo scribe, hoping to preserve an account of his people’s plight in the event a savior should come and free the land, once pure but now defiled in equal parts by technological encroachment and an ever-spreading alien mutagen, from its fate. It makes Tallon IV genuinely feel like a living world with a very real history, and it adds a palpable sense of gravity to your mission without bogging it down through plot twists and exposition.

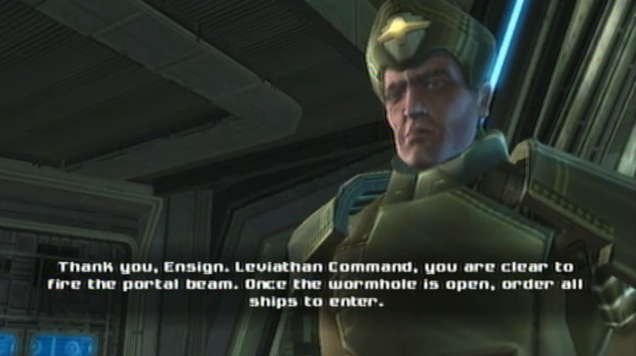

Ironically enough, the Prime series also illustrates how altering this method of storytelling can have adverse effects on a title’s plot and its gameplay. Both of the game’s sequels deviated in their own ways from this approach to narrative, and as a result the two were received much less favorably by fans and critics alike. Where Echoes strayed was in the introduction of the Luminoth race, whose plight was ultimately the reason for Samus’s exploits on the planet Aether. The bounty hunter actively conversed with (or, more specifically, was instructed by) members of the race at every turn in her adventure, and while these interactions were admittedly kept to a minimum, they significantly removed the mystique of Aether. Corruption is even guiltier in this regard, effectively shoehorning a straightforward plot onto the burgeoning sub-series. Here Samus is in regular contact with other non-playable characters throughout the course of the entire game, and while this was (presumably) done in an attempt to make the trilogy’s final chapter an epic on the scale of other space dramas, it failed for a number of reasons, foremost among them being that the storyline came at the expense of the gameplay.

Rather than complement your objectives as it did in the first title (and, to a lesser extent, Echoes), the plot dictated them outright, and because of this it lacked the sense of freedom for which the series is renowned. Even if you deactivated the hint system, you were still told where to go by one of the game’s various authority figures, only further emphasizing how detrimental a more complex story can be to Metroid’s modus operandi if it is not handled with the utmost care. The plot’s omnipresence directly impeded your freedom to explore, not only denying you of your autonomy as the protagonist, but also stripping the worlds you explore of their character. That is not to say they were indistinguishable from one another (each planet was certainly visually distinct, and there were indeed still lore fragments scattered about them to give some insight into their histories), but because Corruption‘s gameplay was so strongly dictated by its linear story, each locale was only a minor footnote in the grander scheme of the narrative and thus were not as fully realized as either Tallon IV or Aether.

More recently, Metroid: Other M received a significant amount of criticism for its approach to storytelling, and while much of this had to do with the game’s themes and its controversial portrayal of Samus (neither of which I will touch upon because both have been discussed ad nauseam), it was also because it hampered the player’s ability to explore the game’s environments. Other M is the most linear of any Metroid title released to date because its progression is dictated by its plot, and gameplay elements were only introduced so long as they satisfied the needs of the story. Rather than complementing one another as they did in Metroid Prime, the two are effectively at odds in Other M and the game struggles to coalesce into a unified and engaging experience as a result.

Of course, I feel I should reiterate that this approach would not benefit all genres of video games, but it at the very least is an interesting solution to the problem of how to handle narrative in an interactive and primarily non-linear medium. Too many titles superimpose a traditional, linear plot onto an open-ended game, and because of this the story loses much of its sense of weight and urgency– after all, what is the hurry to complete an objective if it will just be there waiting for you whenever you should feel like attempting it? This is most decidedly not an ideal approach to narrative in video games, especially if the medium wishes to remove itself from the shadow of the movie industry, a standard to which many developers seem content to aspire towards.

The less a story dictates a title’s gameplay, the better it is for the industry as a whole, and many designers can look to Metroid Prime and other similar games for inspiration on how to effectively design a title without being constrained by the story they wish to tell. Neither element should be subservient to the other in the grander scheme of the experience, but the two should exist in a mutually-beneficial relationship to capitalize on the advantages gaming offers. Say what you will about the “games as art” argument, but if the industry wishes to be taken seriously as viable artistic medium, it needs to forge its own techniques and not rely on those employed by other, incompatible fields.

ShareThis

ShareThis

An excellent article, dear Knezevic. I’ve nothing to add except that I really do enjoy the influence narrative has had on gaming lately– or at least the greater role it’s played in defining the games that we play. It’s not that I like that games have stories, because Prime would be just as good a game if it were just “robogirl who shoots animals”, but rather I like that games are willing to try incorporating story into their games that don’t intrude with the gameplay itself. Things like scanning in Metroid Prime.

Now, if Metroid ever decided to become as heavy-handed with its narrative as, say, Final Fantasy– that’s a different story.

Thank you kindly. :)

It’s exciting to see more games willing to play to the medium’s strengths when it comes to the ways in which they tell their stories. I was originally thinking about using Majora’s Mask as my example, but I couldn’t because I had just written about it. XD