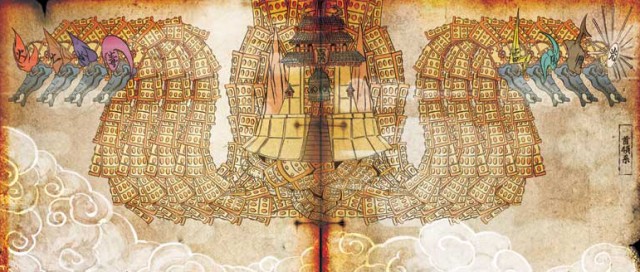

Just one look at Ōkami tells you that it’s a game steeped in Japanese culture. Its unique ink-and-wash art style and cel-shaded graphics don’t waste any time showing off Japan’s rich artistic heritage, and everything from the smallest sparrow to the grandest of cities looks as though it’s been lifted straight out of an ancient, hand-drawn painting.

Yet there’s a lot more to Ōkami than mere appearances, and while its renowned visual aesthetic certainly garnered a lot of praise from both fans and critics alike, it was perhaps the game’s story which left a more lasting impression in players’ minds. With one of the most engaging and highly-crafted narratives in recent years, Ōkami began with the tale of a small village terrorised by the eight-headed serpent Orochi, growing in size and scale to encompass the plight of a dying land ravaged by imps and demons, until eventually the balance of whole world was in danger of being overthrown by the evil and malicious Yami. It was a story of epic proportions, creating a vivid and resonant gaming experience which few games have matched since its release.

But there’s also no denying that within that outstanding story there were just a few moments which seemed a bit bizarre, even for a story straight out of Japan. You know the ones I mean– a bamboo girl from space? Defeating an evil dragon by getting him drunk? One that particularly sticks in my mind was the unexpectedly sinister introduction of Mr. and Mrs. Cutter in Taka Pass. For me, it ranks up there with the first time I innocently ran up to that mad, blood-thirsty piano in Super Mario 64. But if you take a closer look at the underlying Japanese myths and legends that have been woven seamlessly into the game’s narrative, then you’ll find that there’s some method in the madness. For underneath Ōkami’s main plot lies a whole other world of literary allusion you might not have noticed before. For example, the psychotic Cutter couple are actually based off characters from the Japanese folktale “Shita-kiri Suzume” (Tongue-Cut Sparrow). In the same way, even fairly incidental characters like Yoichi the archer and Urashima the fisherman can trace their origins to a number of Japanese fairytales, so let’s stop and take a moment to explore some of those hidden legends– and we might even discover why the futuristic Moon Tribe makes perfect sense in this game based on feudal Japan!

To get our inner literary scholars warmed up, let’s begin with one of the earlier defining moments of the game: when Amaterasu and Susano save Kushi from Orochi. This story arc feeds into several different versions of the same Japanese myth, but you might be surprised by how the game has interpreted the original story.

The legend goes that Izanagi created both Amaterasu and Susanoo when he went to rescue his wife, Izanami, from the underworld. Amaterasu, much like her in-game wolf counterpart, became the Shinto sun goddess, and her brother Susanoo was the Shinto god of storms. But when Susanoo went on a drunken rampage and killed one of his sister’s hand-maidens one day, Amaterasu was so outraged that she sealed herself up in a cave. Darkness fell across the world during this time due to the disappearance of the sun, and it was only when the gods on the Celestial Plain lured her out with a sacred mirror (the “Yata no Kagami”) and some divine jewels (the “Yasakani no Magatama”) that light and peace were restored to the land.

As punishment, Susanoo was banished from the heavens and sent to the province of Izumo. Once there, he met an elderly couple whose daughters had nearly all been eaten by the eight-headed monster, Yamata no Orochi. Their last daughter, Kushinada-hime, was almost due to be taken as the last sacrifice, but Susanoo made a deal with the old couple to give him their daughter’s hand in marriage if he could defeat Orochi. Determined to save her and slay Orochi for good, he transformed Kushinada-hime into a comb to hide her from the beast and told the couple to brew eight flasks of sake. When Orochi arrived to take Kushinada-hime away, the sake proved too good to resist and each head lapped up a whole flask. A very drunk Orochi then promptly began to fall asleep and Susanoo took this opportunity to destroy the monster once and for all by chopping him up into little pieces with his sword.

Many elements of this legend will be very familiar to Ōkami veterans (finally, an explanation for the sake battle technique!), but there are certainly a few unexpected twists to the story as we know it. Susano is indeed a descendant of (Iza)Nagi, but the decision to make both of them human– and have them rely on their respective incarnations of Amaterasu– reinforces one of the game’s major themes– namely that it takes a lot more than a single god to restore the balance of nature. The legend, on the other hand, is a very one-sided affair. Susanoo uses his own cunning to slay Orochi, and while Kushinada-hime’s parents help by brewing the sake, it’s Susanoo who’s calling the shots. In the game, however, Nagi and Susano are completely helpless on their own, as are Ammy and Shiranui, and it’s only when they unite their power that they successfully rid the world of its evils. In the same way, the strong parallels between Nagi and Susano when they finally have to man-up and save the women they love heightens the idea that you don’t have to be a god to be a hero anymore.

Yet for all Ōkami’s efforts to level out the playing field between man and god, the variation on how Amaterasu seals herself away from the world rather slams down the brakes on this notion. Instead of sulking in a cave, it’s the death of Shiranui which extinguishes the light of the sun goddess, and it’s from Shiranui’s statute that Ammy makes her return to the world. Now the way the legend depicts Amaterasu’s reaction to Susanoo’s recklessness makes her seem, let’s face it, a little bit selfish considering the whole world suffers as a result of her tantrum. It’s hardly a very forgiving or god-like response, yet it’s precisely this kind of human reaction that plays into what Ōkami’s development team has done with Susano and Nagi– making the gods more like you and me. But put this in stark contrast to the altogether selfless sacrifice of Shiranui, and a rather miraculous transformation occurs. Amaterasu’s more fallible, human qualities are completely stripped away and she’s presented as little more than an archetypal god character. Then again, she’s also been turned into a wolf, so perhaps this makes up for this apparent U-turn in ideas.

But let’s move on from this legend of high drama and celestial antics to a tale that focuses on a much more diminutive hero. Issun, the pint-sized wandering artist with an eye for the ladies can find his origins in the story of “Issun-bōshi” (One Inch Boy). This folktale tells the adventure of a boy no taller than a man’s fingertip, accurately reflecting Issun’s modest stature in the game. But instead of having ambitions to be the next master artist, Issun-bōshi tries to make his fortune as a miniature samurai, brandishing a trusty needle as his sword. His moment of glory comes when he rescues a princess from a demon carrying a magical mallet. Although the tiny Issun-bōshi is gobbled up and swallowed whole, one prick of his needle-sword is all it takes for the monster to spit him back out again and drop the mallet as it runs away. As a reward for his bravery, the princess uses the mallet to restore Issun-bōshi to normal size and they eventually get married.

Although Issun isn’t quite as lucky with the girls as his literary equivalent, fans will no doubt recognise the mallet as the Lucky Mallet used to miniaturise Ammy in order to gain access to the palace in Sei-an City. Moreover, Ammy’s descent inside the possessed emperor mirrors Issun-bōshi’s encounter with the demon with a very pleasing sense of symmetry. Except there’s one small flaw: the demon has morphed into an emperor and one of the most powerful men in Nippon to boot.

On the one hand this switch could be interpreted as a subtle comment on just how monstrous both our leaders and humans in general can become, as evidenced by the imprisonment of Kaguya for no reason whatsoever. Equally, however, it could suggest that our wrongdoings are actually the result of malicious external forces rather than our own personal failings, as it was Blight who was the root of the emperor’s wickedness. But rather than simply take one side or the other, a combination of both views brings us back full circle to the overarching themes I mentioned earlier: the need for a collaborative effort to maintain the balance of nature. The emperor might not have been acting intentionally, but he still allowed himself to fall under Blight’s spell, emphasising that the game’s message is just as relevant for our leaders as it is for ordinary people like us.

Now before I run the risk of harping on forever about the nuances of Ōkami’s mythological maze, I’ll close with just one more story, namely that of Kaguya herself, the alleged grand-daughter of Mr. Bamboo.

The basis of her character comes from the folktale “Taketori Monogatari” (The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter) and it’s one of literature’s earliest examples of science fiction. The story begins with an old bamboo harvester stumbling upon a shining bamboo stalk. Intrigued, he cuts it open and finds a tiny baby girl inside with shining golden hair. He and his wife rejoice over the arrival of this beautiful girl and they raise her as their own. But one day she sees a full moon and becomes increasingly agitated, revealing that she must return to her people on the moon. Eventually the moon tribe come to take her back to space and she waves a tearful goodbye to her adoptive parents.

Interestingly, some versions of the story say that she was sent to earth in order to protect her from an ongoing celestial war, mimicking the events of Ōkami almost word for word. This myth also goes a long way in explaining the Moon Tribe’s distinctive blonde hair as well as Waka’s connections with the Celestial Plain, and it even allows for Yami’s rebellion against the heavens. In fact, given the number of narrative elements borrowed from this myth, it could be said that Kaguya’s humble tale is actually one of the most fundamental cornerstones of the entire game. Who knew that such a small shoot of bamboo would end up inspiring one of the greatest games ever created?

ShareThis

ShareThis

This was an excellent article, though I probably shouldn’t have read it because I haven’t played Okami yet. :X

Still, it was fascinating to see all of these allusions to Japanese mythology interwoven throughout the narrative, and I know I would’ve missed out on them when I did finally get around to playing the game. Great stuff!

Absolutely fantastic article. Glad to see that someone likes Okami as much as I do (though not as much as Noah since he’s playing through Okamiden three times). It was really interesting, and pretty amazing that the developers used so many Japanese myths and brought them together in the game. Can’t wait for a third Okami.

Very interesting stuff, the japanese tales are so original, thats why anime and japanese videogames are so freaking cool. Love the pictures you choose for the article and that drunken dragon tale.