Back in the late eighties and early nineties, before the modern warfare of today’s online battlefields, there was a console war brewing. Nintendo’s 8 bit NES was in competition with Sega’s powerful Genesis, and both companies were vying for number one position. NES had a healthy market share, but the 16bit Genesis was steadily eating away at the margin, and by 1990 Nintendo were ready to release the fabled SNES (two years after Sega’s Genesis launched in Japan). Improved sound and visual capabilities of SNES (e.g. Mode 7) meant some of Genesis’ features looked dated, and with increased competition from Hudson’s PC Engine in Japan, Sega decided to act. In an effort to combat the CD capabilities of PC Engine/Turbografx 16, and to get one over on the recently released SNES, Sega brought us the MEGA CD, which shipped December 1991. Seeing games on CD was most definitely a novelty back in those days and I remember thinking the possibility of film on a game was awesome! “Finally, real life graphics!”, I somewhat idiotically thought. Of course, after a few viewings of post box sized screens and grainy low quality video the excitement wore of, and the hype around Mega CD soon fizzled out. However this did not stop Nintendo developing their own CD add-on; indeed, they were very close to putting the unit into production at one point, and had a couple of deals with two major technology firms. One of which, was a little Japanese company called Sony, who along with Philips, helped Nintendo develop what would become the ill-fated Super CD.

Before SNES even hit development, a Sony researcher by the name of Ken Kutaragi, had approached Nintendo about designing a sound chip for them, which would outperform what he considered to be the poor performance of NES in regards to its audio capabilities. Eventually a deal was struck between the two companies, and Sony went on to develop the much lauded SPC700 audio chip, which would take pride of place within SNES architecture and be a prominent feature of the console itself, easily bettering the audible efforts of Sega’s Genesis. Part of the deal struck in the late 1980’s (before SNES released) allowed Sony to develop an add-on for SNES (the generational equivalent of Famicom Disk System) for which, Ken Kutaragi suggested Compact Discs be used. Head honchos at Sony were less than pleased with the prospect of helping another rival company, but in the same way they could make cash from selling audio chips to Nintendo, they could from developing hardware for SNES. Sony moved the development of this hardware away from their main “technology” HQ, to an umbrella development team at Sony Music, and so work on the Super CD, or (as it became known internally at Sony) Play Station (two words) for SNES began.

A very early prototype of Sony’s Play Station. Note the SNES cartridge port; also note its enormous size.

What should have been a bright new partnership between two industry powerhouses soon descended into one of the murkiest battles in video game history. There were many designs and versions of Sony’s visions for the system including both standalone, and SNES compatible devices; the medium, however, (CD) was decided relatively early on in development, but even this decision created friction between the two companies. Nintendo, as we know, were extremely paranoid about the threat of piracy. They had increased research into the medium of CD, and decided that a proprietary variation of the CD format was the way forward for the add-on, in order to combat the looming shadow of piracy. This altered Mini-Disc type CD would be called ND, or The Nintendo Disk. It would be housed in a protective shell, and have a lock out chip which would prevent piracy, and use of the software in different regions. Sony meanwhile had other ideas; they wanted the lock out feature to be inside the add-on itself, meaning the games would be normal Compact Discs, something Nintendo most definitely did not want to happen. This internal wrangling led Sony to play the cards Nintendo had dealt them (i.e. a Royal Flush), as during negotiations between the two companies in 1988, Nintendo had inexplicably handed Sony the right to licence all games for Super CD, effectively giving the PlayStation makers every last bit of cash that was to be made off any game released for the add-on.

Prototype N Disk, Nintendo’s medium of choice.

This would have been new territory for Nintendo, as it was their aggressive stance towards game licencing during the NES era which established them as a dominant force in the video game industry. Handing over all profits of Super CD titles to Sony was unimaginable, yet that is exactly what they did, and Sony were ready to capitalize on this oversight by announcing their SNES compatible system to the public. At the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) of 1991 Sony laid out its plans for the newly branded Play Station system, announcing they would licence it broadly to the software and game development industry, thus maximizing the potential revenue they could receive by taking 100% profits from the CD software released for it. Nintendo, who had already foreseen this lopsided deal between themselves and Sony as unsustainable, were working behind Sony’s back, striking a counter deal with Philips (developers of the CDi) to develop the add-on instead of Sony. Nintendo took the particularly harsh move of announcing (the day after Sony’s announcement) at CES that they would in fact be partnering with Philips and not Sony, causing major embarrassment over at Sony HQ. This time the deal between Nintendo and Philips gave all licencing rights to Nintendo, but allowed their IP’s to appear on Philips CDi. Nintendo used the fact that Philips had co-created the CD format as a way of sweetening the deal to the general public, when in reality it was all down to who would be raking in the revenue from software sales.

A prototype of the standalone version of Play Station.

Understandably, Sony were utterly outraged at this U-turn, and threatened to sue the big N if they did not reconsider their actions. This whole situation had put Nintendo in one hell of a predicament. Remember, Sony were still manufacturing the SNES audio chip, and were a company that Nintendo could not afford to make an enemy of given their contributions to Nintendo’s then-flagship piece of hardware. By partnering with Philips, Nintendo had effectively sent a message to Sony. They would attempt to cut off the blood line to their SNES compatible Play Station, by fully supporting Sony’s major rival Philips, ahead of them. All of this cutthroat confusion made Nintendo’s licensees start to worry, as games could not possibly be developed for all of these different systems which all use separate mediums. There was a chance all this uncertainty could put the livelihood of SNES itself at risk, as a potential casualty from all the inter-corporation wrangling. Nintendo knew they would have to renegotiate with Sony and Philips in order to sort this mess out and in 1992 that is exactly what happened.

Nintendo, Sony and Philips managed to strike a deal between them that was thought to be a lot more commercially viable than the unsustainable three way that had previously caused so many problems. A new add-on for SNES would be jointly developed between them, and to appease the worries of licensees and developers, the medium of choice for this new system would be Compact Disc. Nintendo would gain all licencing rights from video games, whilst Sony would have the rights to educational non-video game titles, and Philips retained their rights to have Nintendo games appear on CDi, whilst seeing to it that the add-on itself would be compatible with their console. This new system would slot under the SNES and would be called the “SNES Nintendo Disk Drive.”

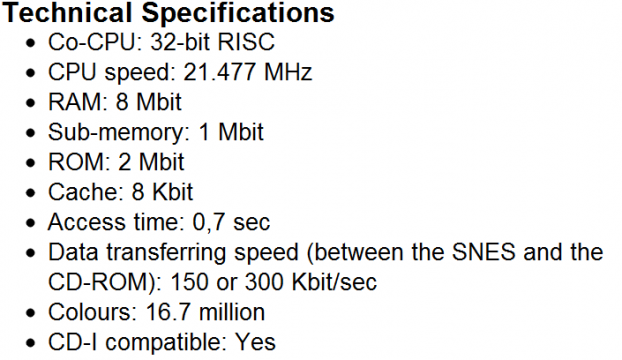

Technical specifications for the system (see above) were released in 1993, with a view to a 1994 release for the now upgraded 32-bit add on. The Nintendo Disk Drive would come with a cartridge which slots into the SNES on top and would be connected via a cable to the actual add-on below, which itself would be connected via the External port on the underside of the Super Nintendo console.

How the redesigned Nintendo/Sony/Philips Super CD would have looked.

Part of the reason Nintendo upgraded the system was down to the 1993 release of their own proprietary Super FX chip. Games like StarFox meant that for any add-on to be a success, it had to be a significant improvement from what was already achievable on a cartridge, hence the step up from 16 to 32 bit. The impending releases of consoles like 3DO and Jaguar would also have impacted the development of the Disk Drive. Nintendo Disk Drive had to be up to scratch, and not just a glorified up-scalar like the floundering Mega CD became.

However, all of these fail safes were not enough for Nintendo to go ahead with production of the now infamous piece of hardware, and by the end of 1993 development of Nintendo Disk Drive had been cancelled. I remember there was a vacuum of news about Super CD at the time. Multi-format magazines stopped covering it altogether as no news at all was released about the system’s demise. All of the time Nintendo, Sony and Philips wasted arguing between themselves ultimately cost the system its chance at life. Development had dragged on for far too long, and even though the system was headed in the right direction, there were still uncertainties at Nintendo about how well SNES could interface with the Disk Drive, given the relatively poor clock speed of the system. (Slower than Sega’s Genesis).

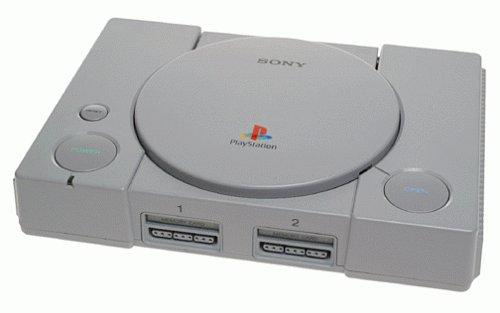

I believe all of these factors, especially the introduction of Super FX, gave Nintendo more than enough reason to abandon development all together. Sony and Philips were pretty much left in the lurch, but both had gained valuable resources from their workings with Nintendo. Philips were able to release Zelda and Mario games for their CDi (let us never speak of them) and Sony of course, took their experience building consoles to the next level by redeveloping Play Station into the brand we now know as PlayStation.

Ken Kutaragi and Sony had become infuriated with the way Nintendo had dangled the proverbial carrot in front of their nose for so long only to repeatedly snatch it away. Sony Computer Entertainment was forged as a subsidiary of Sony Music and they never looked back. The experience gained from working with Nintendo meant it was not long before they had functioning prototypes of their PlayStation vision, and a distribution plan to show off in front of impressed developers. By 1994, major worldwide players such as EA and Namco took notice and immediately confirmed support for the soon to be released console. Sony managed to get one over on Nintendo by announcing games usually associated with Nintendo consoles, like Squaresoft’s Final Fantasy series, which would now only be released on PlayStation. Hype had built up so much prior to its ship date, that by the time Sony’s debut console was released, expectations were at fever pitch. Sony went on to dominate the video game market during the 1990’s and well into the 2000’s until Microsoft’s Xbox (who themselves were helped by SEGA) began to eat away at their market share.

In my opinion, the story of Super CD is surely one of the most interesting in video game history, due to the complexity and outcome of the whole situation. Nintendo’s dominance was effectively broken by their own actions. Scorning Sony so ruthlessly created a beast that could not be controlled. PlayStation became wildly successful, and even though the PS was completely redesigned and rebuilt from the days of SNES compatibility, its ancestry still lies with Nintendo’s 16 bit console. Super CD and PlayStation will always be inextricably linked, and I only hope this article has gone some way to explaining the entangled tale in a comprehensible manner. These are the kind of stories which make the video game industry what it is, and serves as an interesting footnote in the history of Nintendo themselves.

ShareThis

ShareThis

Another good reason why Nintendo doesn’t do business with other platform developers. It never turns out well.

I guess. Once more because of their stupid decision making. THEY are the ones that signed the contract with Sony, giving them the profits of Super CD titles. THEY are the ones that tried to screw over Sony when they realized their OWN mistake. Sony isn’t to blame, nor is anyone else but Nintendo.

In anticipation for the Nintendo Super CD I used to sing about it by using some lyrics from Criss Cross’s Jump:

Somebody try to ROM but they can’t ROM like this,

Somebody try to ROM but they can’t!

What if Nintendo actually did release the Super CD? How would the industry have been different from then up until now?

Its hard to say really, though I do think Sony would still have made a console themselves somewhere down the line. It all depends on how powerful Super CD would really have been. If it had been true 32bit then the system could have changed the whole landscape as we know it today, and maybe PlayStation would still be afilliated with Nintendo?

This is completely off and saddens me that my work was changed into this…

The first bit of detail started off wrong as soon as you said that the NES was in competition with the Genesis…. this is wrong. The Genesis was released early, but was in competition with the SNES. The Master System was technically the 8-bit system of Sega to be in competition with the NES.

Also, the “Super-CD” is a bit off as well. There were 3 different consoles that were in the mix at and around this time. Sony/Nintendo, Philips/Nintendo and finally a Phillips/Nintendo/Sony console.

I’m sorry Greg but the slogan “Genesis does what Nintendon’t” was a direct result of Genesis being in competition with NES, back in the late 1980’s (it is common knowledge Master System and NES were competitors before this) so your wrong on that point.

Super CD is a generic name for the system that was common place back then (at least in UK).If you read you would have noted I mentioned all three of those separate combinations of companies. I think your getting your wires crossed a little.

Just interested in what else is “completely off” in your opinion?