Freedom to explore and get lost is exhilarating; single best modern ambassador of 1980s design sensibilities; Nintendo polish means controls, music, and map design are head and shoulders above its contemporaries; even compared to the rest of its storied series, a unique and essential experience.

English script has problems; like many NES classics, needs to be approached without modern expectations to be understood and appreciated.

Welcome to our inaugural Retro Review! These reviews are contemporary analyses of the classic games in the Nintendo Switch Online libraries of NES and SNES software. We’ve decided to start with one of the greatest games ever made: The Legend of Zelda!

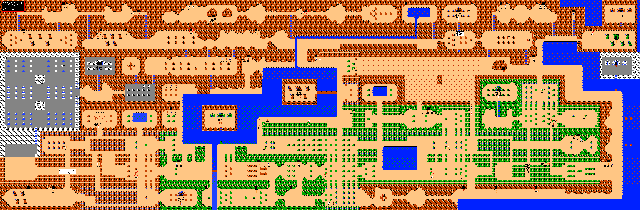

The late 1980s was the golden age of virtual cartography. Illustrated strategy guides were rare, and most forms of persistent in-game assistance (chatty AI sidekicks, minimaps, waypoint markers) were yet to come. Most importantly, the two-dimensional, tile-based games common on both consoles and personal computers were quite amenable to being quickly and accurately represented on graph paper. A generation of players, left to fend for themselves and given the means to do so, created a wealth of hand-drawn maps while patiently navigating the instant classics people now think of as unapproachable — Ultima, Wizardry, Xanadu, and so forth. Some of those maps survive as keepsakes, and others were thrown out like the baseball cards of yore, but while the map itself may be discarded, the actual act of mapping is transformative and indelible, and no game attests this better than 1986’s The Legend of Zelda.

The Legend of Zelda is probably the all-time most hand-mapped video game, based on Google Images search results, and it makes sense. Many other hand-mapping classics, especially those made for a PC audience, were inscrutable and borderline sadistic by design, but the first Zelda game is approachable. Its dungeons are concise mazes of puzzle rooms, building up from the simpler “Eagle” and “Moon” dungeons that can more or less be easily cleared without maps, to the complicated “Lion” and “Skull” dungeons containing networks of confusing bat-filled tunnels under the main areas. In contrast to subsequent Zelda games, the dungeons are largely available to play in a very loose order, so a player may stumble across and explore a harder dungeon, only to bail and return to it later with more resources. It’s all the more reason to commit pen to paper, so that the player can pick things back up when they return.

Later Zelda games make dungeon progression a more regimented and predictable affair — a dungeon will give you Item X, which is used to explore the back half of the dungeon, defeat the boss, and find the next dungeon, where the process repeats with Item Y. This “Zelda formula” wasn’t established until A Link to the Past, which became the reliable series template for a quarter century. In retrospect this makes the first Zelda somewhat unique, both because of the different feel of the dungeons (the player enters not knowing if they’ve got what it takes, rather than knowing the dungeon will provide whatever tool is required), and more importantly because of how it changes the larger structure of the game.

In truth, like Wizardry, The Legend of Zelda consists of a single mega-dungeon — the overworld — which absolutely steals the show. The player is dropped into the overworld in a starting square and is given very little explicit guidance in how to proceed. They poke at the boundaries of their known world, looking for challenges they can overcome and for suspicious terrain that might reveal secrets. Classic elements like Octoroks, Lynels, and bombable walls are all present, but with less tutorializing and telegraphing than in later games. The actual subterranean dungeons containing pieces of the legendary Triforce provide new combat and puzzle rhythms, a grimmer atmosphere, and concrete goals and rewards exclusive to those dungeons, but dungeons in the first Zelda game feel like extensions of the overworld.

Many later Zelda games have segments of the overworld that are closed off from the player and are unlocked only with the appropriate item, serving as exactingly-paced preludes to the main dungeons. In contrast, the original game’s overworld is wide open, immediately rich with possibility, and disinclined to spoon-feed the player any of its secrets. Almost every one of the overworld’s 128 screens is accessible without visiting any dungeon or finding any items. There are NPCs in Hyrule, but they’re all tucked inside caves or dungeons, often behind destructible terrain. In the official English translation, NPCs often provide hints in gibberish (“EASTMOST PENNINSULA IS THE SECRET” being the most famous) and sometimes hidden NPCs even angrily penalize you for finding them. The overall effect is one of loneliness and self-sufficiency, of Link versus the great and hostile wilderness. Go west, young man. Or north, or east. Eventually the player will find a shop, or a dungeon, or another point of interest, and make a note on their map. As the player pushes their frontier outward, they gain mastery, and their map serves as both evidence of that mastery and a tool in further exploration. Nintendo itself seemed to understand the value of homemade maps, based on the inclusion of stylus-scrawled notes in Phantom Hourglass and Spirit Tracks, but the ephemeral nature of pixels just cannot compare to the joy of a tangible map.

Action gameplay in The Legend of Zelda is simple but snappy, and it holds up remarkably well compared to similar titles of the era like Willow, Ys, or Crystalis. Enemy movement and behaviors are tied to background tiles, but Link can move in half-tile increments, which gives the player a slight positional edge despite usually being outnumbered. Learning and exploiting the movement patterns of enemies, and knowing when Link’s sword will repel an enemy, is key to progression, especially once swarms of Blue Darknuts are introduced in the fifth dungeon. Link’s sword size feels fair considering the speed of the enemies, and that’s something that you cannot take for granted with NES-era games. Crystalis and Willow are fine games, but they feel sloppy in comparison, despite having had the chance to learn from The Legend of Zelda‘s example.

From another point of view, because The Legend of Zelda asks more of the player than its sequels do, in conquering the game the player puts more into it, and therefore gets more out of it. The player who expects a smooth modern AAA ride will be served poorly by their own insistence, but they will find a still unique masterpiece if they approach with an open mind, a bit of patience, and perhaps some graph paper.

ShareThis

ShareThis