Robert Marrujo turns thirty years old this year. What was that? You’re here to read about Zelda? Oh, sorry– what I meant to say was that The Legend of Zelda turns thirty years old this year (we’re the same age!). Three decades of games, memories, and milestone achievements have passed in what feels like the blink of an eye since that inaugural release. Zelda has come to mean a lot of different things to a lot of different people over the course of that time. For many, the franchise represents exploration of the unknown, ingenious puzzles, cunning boss battles, thrilling narratives, incredible graphics, and more besides, gaining one of the largest and most devout followings as a result. In celebration of the Legend of Zelda series, let’s take a look at the franchise from its humble beginnings to what it has transformed into today!

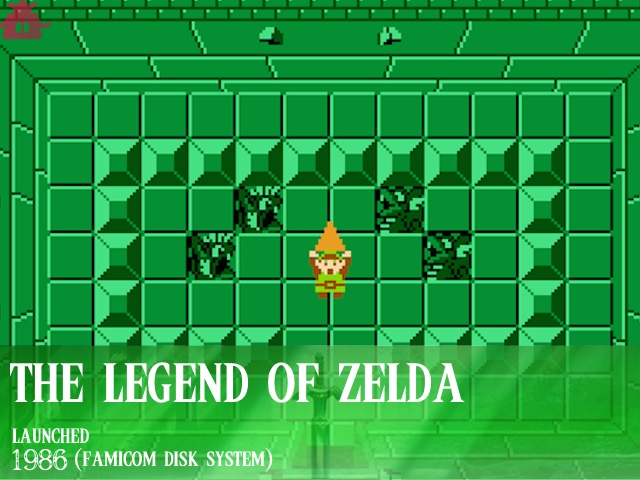

To begin our trek through the history of Zelda, we’re going back to the official first gasp of air that the series ever took, which was not on NES, but the Famicom Disk System, a Japan-only add-on device for Nintendo’s Family Computer that allowed the console to play games straight from floppy disks! The Legend of Zelda set a new standard for video games, taking some of the concepts of exploration that were introduced in the 1979 Atari 2600 title Adventure and expanding upon them exponentially. This game established much of the series as fans know it today, including the trio of Link, Zelda, and Ganon, Hyrule, the Triforce, and much more. This original version of the The Legend of Zelda is actually slightly different from the one that would hit NES in 1987; the music alone has multiple departures to take note of. Check out Clyde Mandelin’s Legends of Localization Book 1: The Legend of Zelda for a thorough breakdown of all the differences between this iteration of the game and the one released on NES!

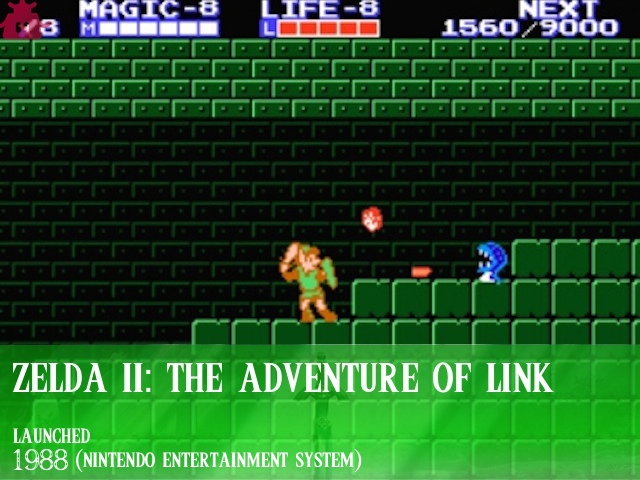

Much like how the Western version of Super Mario Bros. 2 was radically different from the first game, this sequel to The Legend of Zelda marked a shocking shift away from what had come before. Zelda II did feature the top-down perspective of its predecessor, but only for exploration of the overworld map. The bulk of the title’s gameplay instead took place from a 2D platformer viewpoint and introduced some light RPG mechanics like character leveling that have been absent from the series ever since. It’s generally beloved by most fans of the franchise, but Nintendo has never opted to revisit its play style. Regardless, that hasn’t stopped the developer from utilizing some of the other features it introduced here, such as towns with characters to interact with, Dark Link, and more.

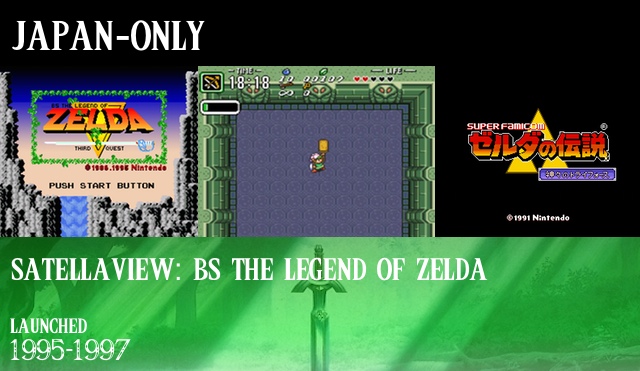

Fans had to wait four years to play the next Zelda game, but it was worth every minute. A Link to the Past wasn’t just a return to the play style of the original, but a milestone of video game development that cemented Zelda as a vanguard of the industry. The environment was huge, with a second, warped version of Hyrule to traverse called the Dark Realm that made exploring the overworld a puzzle unto itself. More mainstays of the series were introduced in A Link to the Past, including Death Mountain and Kakariko Village, as well as themes that Nintendo would return to repeatedly over the years, such as the duality of human nature. It also functioned as an evolutionary leap over the visuals of the two previous titles, establishing something of the cartoony aesthetic that would be further expanded upon in later series entries like The Wind Waker. SNES would only see one Zelda game in the West (Japan was treated to the Satellaview service’s downloadable BS The Legend of Zelda trilogy), but it was enough to hook an entire generation of players, even inspiring many of the greatest minds working in the industry today.

Other than lacking color, it would be easy to mistake Link’s Awakening as a home console installment of the series. After all, its visuals were easily some of the best to ever appear on Game Boy, mimicking the style of A Link to the Past while establishing its own, unique identity (and frankly a better design for Link than on SNES, in this writer’s opinion!). It also came boasting a robust world to explore in the form of Koholint Island and its eight dungeons filled with fiendish puzzles to solve– no small feat for a handheld game released in 1993! Link’s Awakening also came packing an engrossing narrative, one which revolved around the mystery of Koholint and the enigmatic Wind Fish, as well as the budding friendship/maybe-romance between Link and Marin (seriously, Link, when are you going to not be in the friend-zone?). Few portable games of this era could claim to come close to the quality of the titles being released for a home system, but Link’s Awakening was in a league of its own– and arguably still is.

Despite being one of the most popular of Nintendo’s franchises, not every Zelda game has made it beyond Japan’s shores to the rest of the world. Three of those titles were released under the label of “BS The Legend of Zelda,” and were all distributed via the Satellaview satellite service for Super Famicom. In Japan, the Satellaview add-on allowed for Super Famicom to connect to a satellite network and play special Nintendo games that were unavailable elsewhere. Nintendo designed a number of Satellaview titles, including these three Zelda games. One was a remake of The Legend of Zelda that utilized A Link to the Past‘s assets, another was a re-release of A Link to the Past, and the other was something like a “Master Quest,” of sorts, for A Link to the Past starring the male and female mascots of the Satellaview service. The games were released in segments, rather than as whole titles, and included things like a real-time clock, special rewards, and more. Nintendo has never released these games outside of Japan, and it’s highly doubtful that the company ever will, given the unique distribution method for the trio of titles. We don’t have totally official, translated names for the games, but around fan circles they’re commonly referred to as BS The Legend of Zelda, BS The Legend of Zelda: Ancient Stone Tablets, and BS The Legend of Zelda: Triforce of the Gods.

Five years passed before fans would be able to experience another Zelda game, but the title’s infamously long development cycle was necessary to produce such a true masterpiece. Still considered by many to be the pinnacle of the franchise, Ocarina of Time, like The Legend of Zelda before it, is without question a watershed moment in video game development history. Where Super Mario 64 wrote the rules about how to make a 3D adventure game, Ocarina of Time refined and perfected them. Innovations like the title’s lock-on Z-Targeting system provided an elegant solution for camera placement during combat and other activities, one which is recycled and mimicked by developers to this day. Ocarina of Time also made bold strides with storytelling, using its in-game graphics engine to tell a gripping tale of the transformation of a small boy into a young man who would go on to save an entire kingdom. Zelda and Impa were fleshed out in ways that they had never previously been, portrayed as strong characters who would prove invaluable to Link in completing his quest. These and a thousand other reasons besides are why Ocarina of Time is considered to be one of the greatest games ever made, Zelda or otherwise.

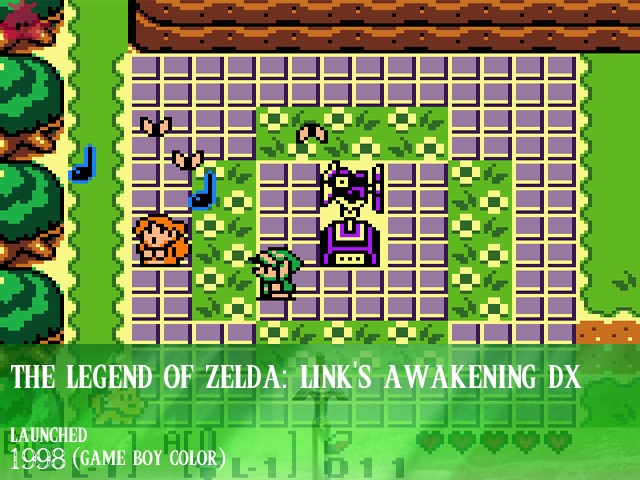

Nintendo gave fans a second tour of Koholint Island with the release of Link’s Awakening DX, and as the company is wont to do, it was a faithful recreation of the original, but with one very important addition: color! Remastered to take advantage of Game Boy Color’s gorgeous chromatic graphics, Link’s Awakening DX provided the same thrills as it did in 1993, but the color overhaul allowed for an even better experience. The game also took advantage of the Game Boy Printer by incorporating a new mouse photographer who would appear for picture opportunities throughout Link’s quest. The photographs were stored in the mouse’s studio in an album, from which players could print them. Along with the Color Dungeon, which could only be accessed if the game was inserted into a Game Boy Color and awarded Link with one of two colored tunics, Link’s Awakening DX was a showpiece of Nintendo’s new handheld and a winning reinvigoration of an already superb title.

Though there’s a two year gap between when Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask were released, the development time for the latter was in reality much closer to only being about a year long. Nintendo was anxious to capitalize on the gargantuan success of Ocarina of Time with a sequel, so in order to help speed things along, the development team would utilize its game engine and much of the same assets to build Majora’s Mask as quickly as possible. Eiji Aonuma stepped into the director’s role for the first time, and under his guidance Nintendo was able to craft one of the most memorable Zelda games ever made. In a bold move, Majora’s Mask employed a 72-hour in-game day/night cycle, with Link using the Ocarina of Time to travel through time and relive the same three days over and over in order to complete his quest. With its implementation of ability-imbuing masks, the exploration of more mature themes, and a darker tone, Majora’s Mask left many players convinced that they’d played the equivalent (if not better) of Ocarina of Time in terms of quality. It might not be as industry-redefining as its predecessor, but Majora’s Mask is an incredible game in its own right.

That concludes part one of our retrospective on the Legend of Zelda series! What thoughts do you have about the games we’ve looked at so far? Sound off in the comments, and come back tomorrow for part two!

ShareThis

ShareThis

It’s always fun to brush up on Zelda history. Am looking forward to part two and what will no doubt be a celebration of the CD-i titles. :)

I agree that the Link design in Link’s Awakening is superior to its SNES counterpart.

However I don’t think Death Mountain was introduced in A Link To The Past. I believe it was present in both NES entries. I could be wrong though as one’s memory starts to go when you’re WAY OLDER THAN 30!