Here’s the second and final part of our interview with Jennifer deWinter, writer of the highly impressive Influential Video Game Designers: Shigeru Miyamoto.

Nintendojo: One element of Miyamoto’s style of game design that I’ve always been impressed by has been his ability to conceptualize titles that are almost always easy for people to learn how to play. In your view, what elements of Miyamoto’s work makes them so intuitive and easy to grasp?

Jennifer deWinter: Miyamoto has an industrial design background. I cannot emphasize this enough when thinking through these types of design choices because this is a field that is always interested in the end user. Miyamoto tests his games extensively, and we get hints of this through his interviews over the years, and in both GDC talks, he discusses this explicitly. His games are not precious— he changes them based on player feedback. So I don’t know what his early games are like. I know that his process ensures that there is enough scaffolding in all of his games that people learn to play them. And he will always design in such a way to reward exploration. That said, Wii Music was a bit of a flop because, according to him, he didn’t convey correctly what people should be able to do. In this way, too, he is player-centric when he reflects on his failures— it’s not the player’s fault if they do not know what is happening. It’s his fault as a designer. This is key to good game design.

ND: There has been talk over the years, particularly when the company was struggling during the GameCube era, of Nintendo abandoning hardware development and becoming a multiplatform software developer. Were Nintendo to ever do this, how much of an impact do you believe such a move would have on Miyamoto as a designer? Would it be more freeing, restricting, or possibly a little bit of both?

JD: I think that Miyamoto would retire. Miyamoto is a special case because he has always been a whole systems designer. One of the things that I really enjoyed reading was the patents that he filed with his teams for hardware innovations. From the beginning, probably because of his early mentor Yokoi, Miyamoto has been thinking through the affordances of hardware on games. Games drive hardware development, and hardware development drives games. His early experiments with controller development naturally led to console development. The consoles and controllers that he helped to create compelled him to create certain types of games to either highlight the capabilities of the hardware or exploit the possibilities of the controller. Think Nintendo 64 and the ways in which Miyamoto helped launch 3D game design by defining what the game camera can and should do both in the game but also how it could be manipulated via the controller.

ND: In your book, you touch on a number of Miyamoto’s more high-profile titles like Ocarina of Time, Wii Sports, and so on, but of his smaller games like the Game Boy title Mole Mania, for instance, which one do you feel stands out as a game that should have been appreciated by more fans? What do you believe is the reason that particular title failed to reach the heights of Miyamoto’s more acclaimed works?

JD: I haven’t played Mole Mania since I was a teenager, so I don’t remember that one as well. I think that there are many reasons that some games take off and others don’t. I was always surprised that Pikmin didn’t take off more as one of his more recent games considering the success of the Nintendogs franchise, but I think that it has more to do with taking care of individual characters (dogs) rather than hoards of characters (Pikmin). It might be because he was trying to do a cute version of Age of Empires, a game mechanic that tends to read as more masculine, in a game that is really targeted to women, but who knows.

ND: Which video game designers will you be focusing on in future installment of Influential Video Game Designer? When should fans expect to read your next book?

JD: I know that we have an excellent lineup of books right now. Carly Kocurek is writing one now on Brenda Laurel, one of the founding members of GDC and hugely influential in the US game industry. On top of that, we have people writing about Gary Gygax, Jane Jensen, Peter Molyneux, Yuu Suzuki, and Roberta Williams. The next one should be coming out in late spring or early summer. We are working with our most excellent publisher at Bloomsbury to finalize the date for the next installment. I recently finished an academic book on Video Game Policy with my co-editor Steven Conway with Routledge Press, and I have just started a new book on Final Fantasy VII, which will probably take another year to complete since I just started visiting the archives.

ND: What are some thoughts that you’d like to share with fans about the video game industry, video games, or Miyamoto that you haven’t said already?

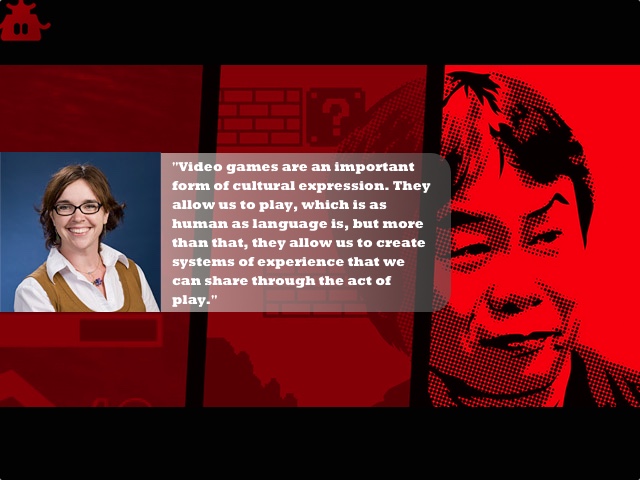

JD: Video games are an important form of cultural expression. They allow us to play, which is as human as language is, but more than that, they allow us to create systems of experience that we can share through the act of play. In the last five years, I have seen an explosion of experimental work in the game industry that uses the affordances of games to tell novel stories, provide new experiences, and bring together multiple people from different geographical and cultural regions. Games are now in important cultural institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian. There are any number of game programs in the US and globally. And the industry is booming, providing people with entertainment but also with art, education, and commentary.

Within this landscape, I hope that people can look to designers like Miyamoto. Why did Miyamoto become influential? Yes, he was in the right place at the right time. Yes, he had particular opportunities provided precisely because he wasn’t a game designer yet. But he becomes influential because his interests are broadly human interests. He experiences joy in his every day world, from exploring in his early games to owning a dog and gardening in his later games. When I think of people who love video games and who want to make video games, I point to Miyamoto, whose inspiration comes not from playing video games, but from using video games to convey multiple lived experiences. And the industry seems to be embracing this approach, using video games to build empathy, connections, and joy.

We’d like to thank Jennifer deWinter for taking the time to let us pick her brain about her book and her thoughts on the video game industry. Click here to get hold of a copy of Influential Video Game Designers: Shigeru Miyamoto, and keep it tuned to Nintendojo for more insights into the world of video games!

ShareThis

ShareThis