The underlying message conveyed in Pokémon Black & White is one that goes beyond moral relativity and attempts the impossible– to seamlessly blend personal ideals with absolute truth, even where the two are clearly in direct contradiction to one another. The basic idea presented is that the dual elements of yin and yang exist in varying proportions in all things, and that, because of this, every person must decide his own right and wrong and realize that each individual’s decision is as veritable as the other.

This concept stems from the legend of the land, which claims that the great dragon Pokémon Reshiram and Zekrom (who in a sense represent virtue and rebellion) were originally one entity. The two of them only split after their twin owners began to stand in opposition to one another in disagreement. After this separation, Reshiram and Zekrom ended up destroying the world in rage, only to recreate it afterward anew. I’m not exactly sure why they did this, or what relevance it holds to the plotline, but I’m guessing Game Freak decided to use this hackneyed story element to express the dragon duo’s gargantuan power levels and perhaps also to display in narrative form the ultimate ramifications of malicious conflict.

But these notions are tainted with much too heavy a dose of foolishness to be adopted wholesale by thinking minds; and quite frankly, overstep several bounds that are just begging to be contradicted.

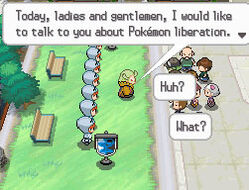

For starters, take the villains of the games, “Team Plasma,” into account. Most of the story revolves around thwarting their undying schemes. But unlike the world tyrants of games past, these foes surprisingly have a much deeper depth to their plight: Mankind is cruel. Pokémon must be liberated.

For starters, take the villains of the games, “Team Plasma,” into account. Most of the story revolves around thwarting their undying schemes. But unlike the world tyrants of games past, these foes surprisingly have a much deeper depth to their plight: Mankind is cruel. Pokémon must be liberated.

But rather than the repetitious, admittedly shallow plight of global conquest, Team Plasma wish to separate mankind from the world they live in. They believe that Pokémon are man’s equals, and should therefore not be used as tools– despite their constant hypocrisy of using them as just that.

Thus begins the war of the worldviews.

During the opening cutscene, Professor Juniper tells the protagonist that he will meet people throughout his journey with different ideas than his, and that this testing of himself, along with his befriending of Pokémon, will allow him to grow as a person and find his place in this world of complementary variables. She believes that the acceptance of diversity is the key to harmony.

However, her politically correct impartation entirely omits that people can be evil. And regardless of all the feel-good nods to love and acceptance coming from the mouths of the protagonists, they, along with the region’s gym leaders, consistently stand in direct opposition of Team Plasma at every turn.

Notice the paradox? If you’re going to preach moral relativism, then it would be wise to leave the idea of including enemies within the immediate spectrum on the outskirts of the chopping board.

A few moments after getting to know Juniper, the hero meets up with Bianca and Cheren, his two childhood friends and makeshift rivals. They haven’t determined what they will be in life yet, with Cheren in particular frequently struggling with the gravity of post-achievement syndrome. What will he do if he does become the Pokémon Champion? Is there a point besides besting the up-hill battle that has been perhaps superficially placed before him? What lies for him beyond the Elite Four?

All that coming from a young teenager. I like how the writers went with realism.

But as another person living in a humanistic world, I can understand his dilemma.

Being a Christian, I am always a wee bit nervous when secular entertainment and media I enjoy present worldviews differing from my own. I have vacillated on how I should respond to this almost daily. My highest conclusion thus far is to hearken to the proverbial “eat the meat and spit out the bones”– which simply means to take the good out and disregard the yuck. Man cannot be defiled from the outside, after all. Defilement can only come from within.

It has been said that you cannot rightly tell a good story without conflict. While this is certainly true, it does not render the coexistence of good and evil equally righteous. One truth can be interpreted differently, but there is nonetheless only one truth. To claim that this is not so is to create a Catch-22 wherein even the most well-intentioned attempts at personal betterment and discovery are rendered nil by the eternal game of beating around the bush that the notion of equivalent opposites so vigorously cleaves to in the all-powerful name of E pluribus unum.

Many consider the search for singular truth and religious beliefs so extreme that they are to be laughed at. But in most societies throughout history, people sought out signs, idols, superstitions, science– yes, even science– to try to get some moral leg up on exactly what was right and what was wrong, especially when it pertained to the treatment of our fellow man.

But Pokémon Black & White, despite Nintendo’s best wishes, only manage to gray the two colors in a fog of inconsistency.

For example, when the hero first meets with Alder, Unova’s Champion, the man immediately gets into a monologue about how there are “different strokes for different folks” and that trainers should always let people use Pokémon in whatever way they see fit. This, to me, is without question one of the stupidest statements I’ve ever seen in a video game.

And after his own discussion with Alder, friend Cheren concludes that “there are as many truths and ideals as there are Pokémon.”

If you apply these two outlandish thoughts with the backdrop of universal acceptance laid throughout the games’ dialogue, then you will quickly realize that, if this is truly the case, then there is absolutely no point in fighting Team Plasma or ending Ghetsis’ totalitarianism.

After all, we should just accept them for who they are, right?

No. As important as compassion is, we need to abandon this postmodern idea that love is the merry, ignorant acceptance of all when saying so decimates the fine line between good and evil. Realizing that liberty and justice are two sides of the same coin is a monumental step in mental achievement.

But let’s not get too worked up over it. At the end of the day, Team Plasma is proven wrong. Trainers are not enslaving their Pokémon pets. And no matter what its inhabitants say, the world of Pokémon is still a place in which there is solitary righteousness, law and order.

Because even within the realms of fiction, there are utter absolutes.

Where’s Officer Jenny when you need her?

ShareThis

ShareThis

Bravo, amazingly enough I read the whole spiel, liked it, and concur.

Thank you. It’s not that I have anything against Pokémon at all – I’ve played happily through every generation thus far. It’s just that I felt I needed to write this article to clarify my own personal feelings towards some of the wishy-washy morals taught in these most recent pair of games.

This was a great read, but I must disagree with it. Team Plasma consistently overstepped the boundaries of their rights. Everyone is certainly entitled to live and use Pokémon as they wish, so long as they do not impede upon or revoke that selfsame right for someone else. I’m sure you will recall how often the group forcefully stole the Pokémon of others; to simply let those actions slide because they’re entitled to do as they wish is horribly unjust to the victims, who also happened to be exercising that right. It is one thing to live by your own ideals, but it is entirely another to use terrorist activity to force them upon others. Unova’s Gym Leaders banding together against Team Plasma (who ultimately amounted to a terrorist group) in no way contradicts the moral of the tale (and this is not even mentioning the fact their “ideals” were littler more than a ruse to cover up their true insidious motives.)

I certainly agree the narrative was heavy-handed, but the underlying message of the plot was tolerance of others and their ideals, not moral relativism. None of Team Plasma’s public demonstrations were ever broken up; only when they resorted to theft and physical intimidation did an authoritative figure intercede.

Most of Team Plasma did not have insidious motives. They were simply playing follow the leader. It was really only the sage Ghetsis who used the organization to further his ulterior cause. Most of them, including the leader N, were innocent as far as terror is considered. In their minds they were just doing what they felt was right.

But that doesn’t make them right. And that’s where the games’ underlying message of “to each his own” falls hard.

Besides, if Reshiram (Truth) and Zekrom (Ideals) are equal, then how can anyone say that anyone is wrong? Since this generation of games refused to discuss absolutes and consequences, all rights expressed must have been determined by the majority. And if all rights are determined by the majority, then Ghetsis was doing nothing wrong in his plan of wooing the majority over to his side in order to fulfill his (dare I say it) evil intentions.

The moral presented in B&W is really one of validating IMOs, which is endless and doesn’t solve a thing.

Gold & Silver’s rival trainer’s neglect and abuse of his own Pokémon was immoral – and it was presented that way.

But if we take Black & White’s indeterminable moral into account, his ultimate redemption at the end of the game was only him moving from one truth and ideal (hate) to another (love).

Your article has some intriguing points but the whole concept falls down on the pretense that you assume that Team Plasma are inherently evil from the outset. Team Plasma are painted as being ideological and act in accorandance with this ideology. The wrongs they commit are not born from evil but from idealism and it is only with truth (notice where these words feature in the game?) can the player reveal that good intentions can hide a malicious intent. The actions of Team Plasma are thwarted but they are never silenced, never segregated. They are given their right to speak and only when they reveal their true plans are their swiftly brought to justice.

And this is the idea behind this game. The whole point of Black and White’s narrative is that there isn’t supposed to be a clear moral stance between Team Plasma and the protagonists. Throughout the game, the player isn’t bullied by any authority figures into disagreeing with Plasma, they can listen to their argument’s fully and openly. The game’s vision of equality encourages personal opinion and freedom of choice rather than a lawless terrain of immorality.

Pokémon theft aside, Team Plasma aren’t painted as criminals but extremist activists. Didn’t you feel at times throughout your journey that, wait, maybe they do have a point? It isn’t supposed to be simply black and white, it’s supposed to be deeper than previous Pokémon games. It’s not until the very end when we discover that Plasma have been as deceptive and malicious as every other evil organisation in the Pokémon world.

(And it’s not just Ghestis, a Plasma grunt in the castle cruelfully jokes how they’ve been fooling people into releasing their Pokémon when Team Plasma have been forcing their own Pokémon to build their fortress. The player is supposed to have been as duped by this moral facade as the rest of the people of Unova.)

I think a few of your arguments could be strengthened by being expressed in clearer language but all I would say in conclusion is that I thoroughly object to the condemnation of any attempt to spread a message of acceptance and equality in any form of art, including gaming. Team Plasma don’t think quite so differently to the heroes of Black and White, the fact is that N is merely a misguided trainer with deep care for Pokémon. Shoving him out the door and labelling him as a enemy of the community would paint the protagonists as simply sporting a militant attitude and you have to remember that the message of this game not only relates to Unova but to the real world and it’s a message that’s being taken on by young children as well as core gamers.

If a Pokémon game is trying to say to kids that “diversity is the key to harmony” then surely that should be celebrated? No franchise with the young audience and sheer market weight of Pokémon has tried to spread a message of acceptance in quite this way before and I don’t think picking holes in the perceived morality of Team Plasma is the best angle to take on the subject. Juniper doesn’t tell the protagonists to ignore wrong doing, she encourages an open mindedness within them. She says that just beause some people don’t agree with you, doesn’t make them bad people. Now, as an atheist, I would say that’s a pretty powerful message to take from a game aimed at seven-year-olds and it’s one that can only help breed understanding and equality in modern society. Just because we might assume someone is bad, it doesn’t give us the right to condemn them and segregate them.

Adam, the only two views presented in Pokémon Black & White are to train Pokémon and to release Pokémon. They never get into any deeper morals besides those, and the dozens of characters blabbering on about it throughout the games as if they did achieve some incredible insight is really annoying. Sure, there’s a woman who hates noise who lives alone in a trailer and a couple of black trainers – but those hardly qualify as thought-provoking diversity.

The Champion Alder, who frequently talks about love, acceptance, and letting anyone use Pokémon in any way they see fit, ends up telling N that he’s just “a brat with ridiculous dreams.” But a couple scenes later, right before the credits roll, he tells N and the player that there is no right or wrong opinions, though that’s exactly what he was standing against just moments earlier.

It’s really a tragic oxymoron in the B&W worldview. The characters in the games’ morals end up flip-flopping more than a catfish in a moon bounce.

While you may have a point, quoting Hannah Montanna is not going to strengthen your argument Smith.

And I would disagree with that, the whole point of the game’s message is to think before you judge someone. To look at all the facts and then formulate your opinion based on your personal views but also fairness. Alder has a vision of equality for Pokémon and people but just because he believes that doesn’t mean he surrenders the right to condemn the villainous. And I think you’re completely ignoring the massive emotional epiphany N goes through at the end of the game. Alder can say N is wrong and selfish but he can’t say his opinion is worthless, he never says that.

The characters in Black and White are allowed to have opinions about people, they just don’t need to force them down anyone’s throats. Sure, the world isn’t overflowing with every complex minority and social cleavage because it’s a game aimed at children. The important thing is that the message is there, don’t judge someone before you understand their motivations. That many people are not evil, just different.

Isn’t that essentially what Elesa says to Bianca? Or am I just imprinting an equality message onto someone who is a blatant homage to Lady Gaga?

You caught my quote! (Lol)!!

But Alder does harshly shred N behind his back after losing to him. And he also called Team Plasma a bunch of liars while he was in Iris’ city.

And Lady Gaga, I’mean, Elesa’s stint with Bianca was a very poor moral in reality. Teaching real-life tweens that they should live on their own without any parental supervision is ridonculously absurd. In the PKMN world, it’s fine to leave home at ten or eleven; but that shouldn’t transmit, as it surely will through the minds of American children, over into the human world.

I thank you for your comments, Adam.

I wasn’t meaning that children should attempt to leave home, that’s not the point at all. The game isn’t trying to tell children to run away from home or anything like that, it’s encouraging them to be who they want to be. To discover themselves in their own way and feel empowered. To not be defined by the opinions of others, to be true to themselves.

And when you add that message to Juniper’s “diversity is the key to harmony” speech, and acknowledge the fact that Elesa is a Lady Gaga homage living in a city that has a musical theatre, I think it’s pretty fair to say that the game has a fairly pro-gay, pro-equality message going on.

Maybe that’s why this game has a strong personal connection between N and the main character? The emotional bond exhibited between the two is more than a bitter rivalry, it’s an emotional connection unseen anywhere else in the franchise. The isolation of the two during the ferris wheel is a fairly obvious example, even if it’s completely unsaid.

That is the true meaning of Black and White, it runs through everything I’ve said here. Even if you don’t agree with someone’s opinions and actions, they deserve the right to act in whatever way they wish as long as they don’t affect the lives of others. And that is a message worth teaching to children.

If you’re gonna talk homosexuality, I think the effeminate Burgh with all his man-clowns living in a giant honeycomb would make the prime example. *_*

And Bianca leaving home against her father’s will was the whole point of her talk with Elesa. I found the complete stranger Elesa telling Bianca’s dad off as if he is some terrible parent to be very disturbing and anti-family – even though I don’t believe that was Game Freak’s intentions.

And the game’s narrative never states that it’s okay to be anything you want so long as it doesn’t affect anyone negatively. It just goes without saying, I believe, because it would dampen their rather humanistic morals if they were to separate good and evil. That’s one of my greatest concerns, as B&W have absolutely no basis for telling me why it’s wrong for a megalomaniac to try and take over the world. They just assume that you have to agree because they can’t explain why the bad guys shouldn’t be bad. I mean, if it’s who they are, we should just embrace it, right?

The moral “be yourself” works two ways, allowing room for a young boy to aspire to be a football quarterback and a lying thief to continue working his trade, as long as they both feel good about it. This theme presented in B&W of diversity and unity is so vague that it is blurred, and I have a problem with that.

I’m going to email you about this, I don’t think the comments section is the best venue for our discussion any longer.

Thank you guys for the insightful commentary. There was a lot I agreed and disagreed with in both of your arguments, but while I may not agree with the entirety of the message of the game, I will say that one of the best things about B&W was that it wasn’t afraid to try and explore the difficulties of moral relativism. It definitely shows that the series is growing up.

I feel I should clarify one of my more “hazy” sentences from paragraph #13.

“E pluribus unum,” as you may know, means “Out of many, one.” It is an American motto written on currency. But if you look at the bigger picture, it can also be taken as a statement of universalism.

What I mean by speaking against universalism is that its message of “everything goes” makes it impossible to even try to become a better person and trivializes learning when it states that all ideas and opinions are just as good as any other. It solves nothing and is only there to make people feel good about themselves.