DISCLAIMER: Spoilers of different games in the Zelda series to follow.

“IT’S DANGEROUS TO GO ALONE! TAKE THIS.”

So begins NES’s 1986 landmark, The Legend of Zelda. “This” turns out to be a wooden sword, the first acquisition of the first game in a series that has spent the last thirty years dispensing piles of weapons, accessories, equipment, and utility items to fans worldwide.

This moment in itself marked a true revolution in the home console experience. Up to that point, most game system experiences were pretty basic; if you wanted anything other than rote hack-and-slash you had to get a computer… and computers, adjusted for inflation, ran into the thousands of dollars. But what Nintendo did with Zelda— and, later that year, with Metroid— was about much more than the acquisition of virtual equipment.

It was about adventure. And the stuff you gathered along the way was just the means.

The core premise of the first Zelda, and every game in the series thereafter, is this: turn an everyman hero (Link) loose on a large, diverse, open world. But don’t let him explore it all at once. Gatekeep it. Make him earn the right to go places. Make him find the keys– either literal or proverbial– that open up those places. Then, once he arrives at new places, reward him for his trouble, then coax him out the door and onto even more new places, each with their own gates.

The gates could be anything: a body of water, a giant rock, or some towering monster. And the keys could, likewise, be anything: a bomb, a grappling hook, a musical instrument, or a swank heat-resistant red suit. Putting the two together could be as simple an exercise in getting item A to point B. Or it could be as complex as a labyrinthine path across a complex puzzle while in the form of a dark wolf.

Link, maybe more than any character in video game history, is as much as an explorer as he is a hero. His path is one of undiscovered countries. In the SNES classic A Link to the Past, Link stumbles into a parallel world, at first just at a glimpse, and then later (once he acquires the ability to repel the dark world’s transformational curses) for long stretches of time. Later in that game Link comes across a forbidding sign that points to Misery Mire, declaring: “No Entry. No Escape.” Of course, this sign just begs for Link to reach this haunted place, and later on he does.

Each successive Zelda game pushes the bounds of the frontier. In N64’s Ocarina of Time, for example, Link pulls a sword from a stone and finds himself transported into an older body in a twisted future. Link gets to experience both the wonder of running through (and later, riding on horseback across) this new future, and the pain of seeing how darkness has tainted this dystopian realm.

The sequel to Ocarina, Majora’s Mask, presses the theme of time by landing Link in a world where the end of all things is just three days away. Going back to the start of the three-day period is possible (and necessary) but Link loses certain disposable items and the memories of others around him if he does. I will not soon forget finishing a quest with just thirty seconds left until the apocalypse, making my peace with a character before whisking back, once more, to the start of the three-day period… nor will I forget arriving at the great tree that lies beyond the final day.

GameCube’s cel-shaded Wind Waker moved Link to the open seas. The game was set entirely upon islands in a vast ocean, the wind at his back as he explored a succession of towns, grottoes, and dungeons. A pivotal moment came late in the game when Link stumbled upon an underwater palace that harkened back to the many moments in Ocarina of Time. I will not soon forget watching the cel-shaded Link taking in the visual stories of his N64 predecessor.

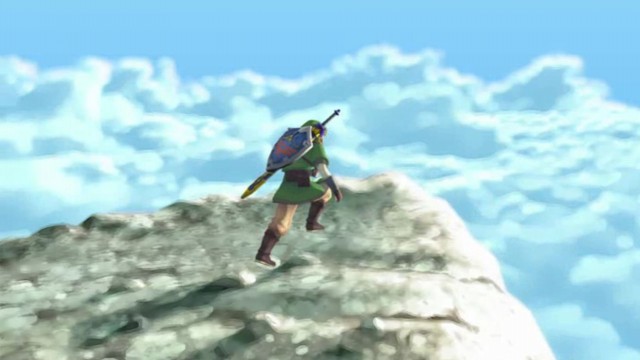

And so it goes on, both on Nintendo’s consoles and on its handhelds. Link’s adventures take him to islands created in the dreams of monsters, through corrupted realms of shadow, into microscopic civilizations, and along landscapes punctuated by train tracks. Link voyages to water temples at the bottom of the ocean and, on the back of a flying bird, to empires aloft in the sky. Not all Zelda games push the envelope to the same degree, but all of them open new doors in some fashion.

True action-adventures like Zelda are fewer in number than they once were, especially as the open-world concept has become more and more the province of role-playing, especially in the form of Western RPGs. That hasn’t stopped Nintendo from crafting new adventures for Link, or gamers from playing them.

Here’s to another thirty years of passing through more gates and emerging into new worlds.

ShareThis

ShareThis