This week’s release of Epic Mickey marks a momentous event for the video games industry: one of the season’s most highly anticipated titles doesn’t come from a publishing powerhouse like Nintendo or Activision. Rather, it comes from Disney, a long-time player in video games that has never held center stage before. Disney is one of a handful of media companies that have tried to make an impact in the video game software space in the past 30 years. The past five years have represented the most significant step forward for them, but will these companies have the staying power required to make a lasting presence?

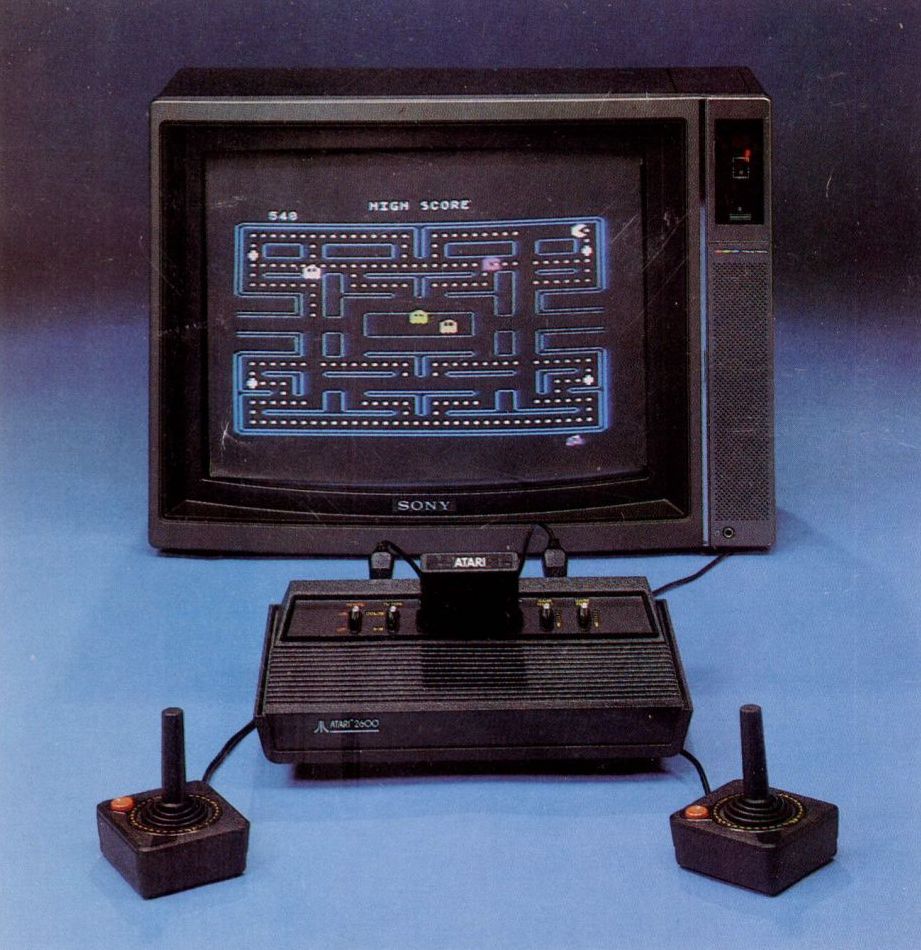

The first significant step came in 1976 when Warner Communications purchased the fledgling startup Atari for $28 million (and a promise to fund Atari founder Nolan Bushnell’s concept restaurant featuring games, pizza and electronic animals, among other things). While Atari had already become a household name thanks to the wildly popular success of its Pong arcade systems, the company enjoyed its greatest success under the ownership of its media parent. In 1977, the Atari 2600, the progenitor of modern console gaming, was released and became the company’s best-selling console of all time, selling over 30 million units. The Atari 2600 jump-started the American home console video game industry and at one point accounted for one-third of Warner Communication’s total profits.

The first significant step came in 1976 when Warner Communications purchased the fledgling startup Atari for $28 million (and a promise to fund Atari founder Nolan Bushnell’s concept restaurant featuring games, pizza and electronic animals, among other things). While Atari had already become a household name thanks to the wildly popular success of its Pong arcade systems, the company enjoyed its greatest success under the ownership of its media parent. In 1977, the Atari 2600, the progenitor of modern console gaming, was released and became the company’s best-selling console of all time, selling over 30 million units. The Atari 2600 jump-started the American home console video game industry and at one point accounted for one-third of Warner Communication’s total profits.

The good times didn’t last, however, as Atari ran into numerous problems leading to the infamous video games market crash of 1983. While Atari had earned Warner Communications $415 million in revenue by 1980, the company had created profit losses of $533 million by 1983. Warner’s stock fell by two-thirds from $60 to $20 per share and the media industry was put on notice about the uncertainties of this new business.

In the meantime, Nintendo was preparing to launch the Game & Watch and reached an agreement with Disney to use the Mickey Mouse license to produce games for its new system. At the time, Disney was just preparing to launch Disney Home Video and the Disney Channel and was eager to expose its brands through other products. Between 1981 and 1984, Gunpei Yokoi’s famed Nintendo R&D 1 studio developed released three Mickey Mouse games for the Game & Watch. Building on this success, Disney continued licensing its characters to video game companies letting Hudson Soft, Sierra Entertainment and Capcom develop and publish four additional games between 1985 and 1987.

In 1988, Disney formally acknowledged the increasing importance of video games to its business with the creation of Walt Disney Computer Software. That same year, the new studio developed two games, Matterhorn Screamer and The Chase on Tom Sawyer’s Island and published another two,  Donald’s Alphabet Soup and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. While the company had the capabilities to develop its own software, the company focused on licensing its brands to established video game developers. This model saw its greatest success with DuckTales for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Using Disney’s Duck universe and Capcom’s Mega Man team as developers, DuckTales was both a commercial success and a fan favorite on the NES.

Donald’s Alphabet Soup and Who Framed Roger Rabbit. While the company had the capabilities to develop its own software, the company focused on licensing its brands to established video game developers. This model saw its greatest success with DuckTales for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Using Disney’s Duck universe and Capcom’s Mega Man team as developers, DuckTales was both a commercial success and a fan favorite on the NES.

Through the 1990s, well over 40 Disney games were published for various platforms. Famously, Disney games also launched the career of future Resident Evil creator Shinji Mikami. The Walt Disney Computer Software company was officially shut down in 1996 but was quickly reformed as Disney Interactive as part of an internal reorganization.

Unable to ignore the high growth prospects of the video games industry, Disney was joined by their fellow media competitors Viacom and the newly formed Time Warner during this time period. Recognizing they lacked the internal talent and resources needed to create full-fledged studios, these companies followed Disney’s model and formed partnerships with western publishing giants such as Electronic Arts, Activision and THQ.

While these techniques allowed their established media icons to gain presence in the industry with little of their own effort, the results weren’t completely satisfying. Licensed games became synonymous with low quality. Publishers complained about having to rush titles to meet theatrical release dates while media companies were annoyed with the tarnishing of their brand and the potential profits that they were missing out on. With a booming economy in the mid-2000s, media companies decided to take action to internalize video game development through a series of high-profile acquisitions. Viacom purchased Guitar Hero maker Harmonix in 2006, Vivendi merged its Blizzard Entertainment division with Activision in 2007 and Warner Bros. bought Midway’s remaining assets in 2009.

While these techniques allowed their established media icons to gain presence in the industry with little of their own effort, the results weren’t completely satisfying. Licensed games became synonymous with low quality. Publishers complained about having to rush titles to meet theatrical release dates while media companies were annoyed with the tarnishing of their brand and the potential profits that they were missing out on. With a booming economy in the mid-2000s, media companies decided to take action to internalize video game development through a series of high-profile acquisitions. Viacom purchased Guitar Hero maker Harmonix in 2006, Vivendi merged its Blizzard Entertainment division with Activision in 2007 and Warner Bros. bought Midway’s remaining assets in 2009.

Disney continued to lead the way, acquiring nine studios between 2005 and 2010, including Warren Spector’s Junction Point Studios, the future developers of Epic Mickey. Disney also took on new roles by splitting off the Buena Vista Interactive brand from Disney Interactive to publish titles such as Lumines, a Disney version of Meteos and the Kingdom Hearts series. Since then, Buena Vista merged back into Disney Interactive to become Disney Interactive Studios in its present form.

While the major media companies took large steps in the mid-2000s to establish their presence in video games, recent developments have begun to raise more questions. Despite the critical success of Rock Band 3, Viacom announced that it is planning to sell Harmonix and exit out of the console games segment. Despite initially giving support to Epic Mickey, Disney’s top brass have publicly stated recently that the console business appears too risky and that they are shifting resources to digital releases and the social gaming space. In a series of moves, Disney acquired social game maker Playdom, acquired iPhone game maker Tapulous, promoted Playdom to become co-President of Disney Interactive Media Group and let go of Disney Interactive Studio’s chief executive of the past 8 years, Graham Hopper.

At the same time, Warner Bros. purchased Batman: Arkham Asylum developer Rocksteady studios last February and is preparing for the release of Arkham City in 2011. Vivendi’s investment in the Activision Blizzard merger appears to have worked well for the company so far. Media companies possess advantages in the video game industry due to their large size and number of recognizable brands but have lacked the experience of the top players like Nintendo and Activision or the risk appetite of smaller studios and startups. And until they are willing to make a change, these media companies will continue to struggle establishing themselves in the home console space.

ShareThis

ShareThis