|

“What role does gender play in The Legend of Zelda franchise?” An interesting question, no doubt, and perhaps one the gaming industry has overlooked for too long. Sure, the portrayal of the male and female in the realm of Hyrule seems fairly routine upon first inspection (and those of us intrigued by sexuality in gaming have long been far too easily tempted with the more obvious bait of the Princess Peaches, Samus Arans and Bayonettas of this world) but after looking at the state of feminism in other parts of the video game world, the question of Zelda kept coming back to me. Kept me awake as I tried to doze off at night, kept forcing me to get out of bed and jot down unrelated and bizarre notes on Link’s feminine attributes before I could actually sleep.

And, perhaps most importantly, kept flooding my thoughts any time a lecturer at university brought up the issue of gender in relation to the novel Orlando by Virginia Woolf. Not only did the story tell of a noble warrior who remained ever youthful throughout hundreds of years of monumental history but this chosen soul, the eponymous Orlando, miraculously changed gender partway through the narrative and changed from man to woman. While his/her physiology had been irreversibly altered somehow, the intrinsic nature and identity of Orlando remained stable and unaltered, forcing us to consider where our identity ends and our gender begins. Naturally as this was all happening in the lecture, I was busy penning notes of Sheik and Tetra, try to form some kind of solid theory on the franchise.

When a fellow student swaggered over to me in the union bar at 3am dressed in a toga (there was context to this, it wasn’t a very bizarre dream) and said that they liked all my previous work on the subject of gender roles in video games but was interested to hear my thoughts on the Zelda franchise in relation, I took it as a sign that this question finally needed tackling.

So let’s do it. For while we may not realise it at first, The Legend of Zelda is one of the most interesting and unique video game series in terms of gender roles and the fact that it doesn’t immediately come to mind as such is all the more interesting. For all the talk of Princess Peach’s long running status as little more than a post-modern damsel or Samus’s status as the lone icon of feminist gaming, the Zelda franchise offers up a veritable banquet of food for thought that goes well beyond of the initial fan boy concerns of whether or not Zelda becomes a dude when she turns into Sheik.

We’ve all had those moments when we’ve been confused about our feelings. Haven’t we?

(While the Zelda/Sheik gender puzzle is the most prevalent gender concern among the Zelda community, it is by no means the most interesting topic of discussion from a gender perspective. If anything, I’d wager it being more of an underlying paranoia that if Sheik was actually male then their unspoken crushes on the empowered character would become weird and wrong. Just for the record guys, he/she isn’t real so it’s still wrong.)

I think a much more fitting place to begin is Link, the centre of the series’ narrative. The born again Hero of Time that must fight to save Hyrule from the forces of darkness. That guy over there in the green skirt (sorry, tunic). While Link’s initial appearance may come come across as effeminate (even though there’s no denying that Link works the long blonde hair and green knee-length number) he is unequivocally a male character in a male-dominated world. And while wider trends may have begun to increase the presence of women in gaming in recent years, unless you’re Activision, I think it would be fair to argue that Link’s masculinity is much less an integral aspect of his nature than a situation of convenience. In some ways, video games give us the chance to study the living artefacts of social history as we analyse how crudely formed, simplistic characters from 25 years ago have been almost unwillingly dragged into modern culture.

If the likes of Link or Mario had been literary characters (A Tale of Two Warp Pipes, anyone?) then they would have been fully formed, published and then archived into the annals of history, where they would likely inspire future characters that would build on their legacy in a more modern context. However, video games work in a very different way in a sense that they have been highly monetized from their genesis. While literature existed for thousand of years as a largely personal venture, the pursuit of profit made the early successes of the media hot tickets to be nurtured and sequelized. Even today, a Legend of Zelda game will sell invariably more copies than an equally good title based on an original property, even if the latter has a lot more in common with the social ideas of today as opposed to twenty-five years ago. The fact is that Link is a character at the helm of a franchise that has existed well beyond its years, only managing to maintain some form of social relevance with a multitude of multitude of adjustments and a subtle rebalancing of its characters. It’s like foregoing a washing machine and using a mangle with an electric motor attached to wash your clothes: painfully antiquated but still somewhat useful in modern life.

When you look at Wind Waker Link, the first word that comes to mind is more likely to be “cute” than “masculine.”

With that in mind, I think we can safely separate Link’s nature from his gender. What I hope to argue is that Link’s personality is both distinct from and potentially even conflicting with his masculinity and to do that we must accept that we are analysing the evolution of a defunct character that has only been maintained through chance. If Link was being conceived today as a fully formed character, how different would he be? I highly doubt Nintendo would have made Link female even if they had could have done so (the 1980s world of Japanese gaming hardly sounded like a forefront of feminist progression), but just how different is he from the quintessential male action lead in spite of this?

When you think about the kind of character that Link is, some intriguing thoughts come to mind. While his innocence, bravery and purity are all defining aspects of his character (to the point where he is often portrayed as being a young child), Link’s passivity, his all-round obliviousness to his situation, the fact that he is typically reactive in his behaviour; these all seem to be more female traits than male. Even his trademark stoic nature seems to play to the antiquated idea that women (and children) should be seen and not heard. Link is a hero of destiny, his quest is never self imposed and he is always guided from one temple to another where he is told more and more of his duty to his people; can we really accept Link as a male hero when he seems to fill the typically female role of reaction, acceptance and innocence?

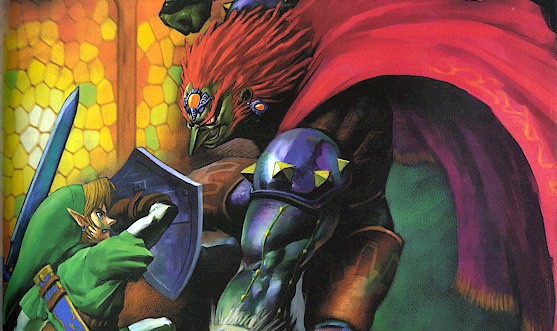

On the other hand is Ganondorf, a ruthless, dominant figure that seems surprisingly connected to his gender for a character that started out life as a demonic pig. While his portrayal has varied throughout the Zelda series, we are repeatedly brought back to his innate wickedness but also his justifications for such cruelty. Does his masculinity legitimize his power-hungry nature in our eyes? If he was a woman, would we as an audience look upon him differently? Certainly, both society and the history of narrative has conditioned us to paint conceptions of desperation, envy, selfishness and loneliness onto evil female characters (or conversely strip them of their very feminine nature, circa Lady Macbeth) but we do none of this with Ganondorf.

On the contrary, Ganondorf appears to be one of gaming’s most respected villains (if such a status exists) and his gender almost gives him a prerogative to carry such acts. The broken man at the end of Wind Waker is neither a one-dimensional antagonist among the ranks of Bowser or those aliens in Space Invaders and nor is he some gender-bending bunny boiler channelling Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction; he is a villain who commands respect of both his power and potential. It is quite the anomaly that Ganondorf’s behaviour is virtually justified by his sex but in contrast, Link’s is somewhat negated.

The Zelda franchise has often played up the differences between Link and Ganondorf, not least their phyiscality.

And then there’s Zelda. The single character of the Zelda franchise that could easily merit an entire string of an articles purely upon her relationship with gender. The isolated, somewhat emotionless monarch that spent the vast majority of her time locked away for the sake of her people, Princess Zelda turned the franchise on its head in Ocarina of Time as she emerged as her secret alter ego: Sheik. Not only was Sheik a far cry from the perfect princess image that Nintendo had spent a number of years cultivating across its franchises, the jarring concept of the helpless Zelda and the ass-kicking Sheik being one and the same caused ripples in the wider community. How did Zelda appear significantly more muscular when she transformed into her alter ego? We knew the process was magical (and also drew into question why we’d been protecting a woman who had the skills of a deathly ninja for the past however many games) but the idea that Zelda could have turned herself into a man for her own protection continues to cause debate to this day.

And while some fans debate that Zelda used bindings to flatten her chest and padding to broaden her shoulders and appear more muscular (I do repeat — “it’s just a game”), it doesn’t explain away the fact there’s still a lack of cohesion between Zelda and Sheik. When I think of Sheik, I think of a fiercely independent woman that can take care of herself but those thoughts don’t resonate across to Zelda, forever helpless. Maybe it’s another inequality of gender in narrative? Why can Ganondorf be accepted fairly easily as both human and demonic beast but we can’t even transfer the personality of two female personas into the one character?

The same thing happened with Zelda’s second alter ego, Tetra. While Link actively travelled and communicated with the young pirate girl for the first half of his adventure, the moment that it was revealed that Tetra was actually Princess Zelda in hiding, a secret even to herself, she was forced to remain in Hyrule Castle until the final battle began. If Zelda is capable of such fierce individualism on her own (Tetra took no prisoners, captaining a crew of burly courtiers) then why is it that every time her true identity is revealed this emotional capital isn’t retained? For all we may admire or respect the characters of Sheik or Tetra, they feel distinctly attached from Zelda to the point where she doesn’t even have control over her own identities.

And that neatly brings me back to Orlando, the novel that started this entire thought process. While I found it to be somewhat flawed in execution (what could have been a thorough exploration of gender ended up being weighed with around forty metric tonnes of imagery) the book does throw up a lot of interesting ideas in relation to Zelda (even more than Shakespeare!). The fact that the central character Orlando changes gender partway through the novel has obvious connections to the alter egos of Princess Zelda, especially in the fact that neither of them are portrayed as coming through their transformation with an altered personality. It wasn’t a change of gender that troubled Orlando (that seemed particularly banal to her) but it was how she had to change her behaviour in Renaissance Europe in response to her new identity that proved most interesting. Is Zelda doing anything different? Perhaps Zelda feels she must play up to such a roll of restrained fragility, even when she is more than capable of acting otherwise.

There’s no easy way to conclude on such arguments but I’ll try and give it a go. If Link seems to be odds with his sexuality and Ganondorf embraces his, is Zelda in direct conflict with hers? Do we see the bearers of the Triforce as some dysfunctional family unit with Ganondorf as the vengeful father, Zelda as the reactive mother and Link as the oblivious child? Even if you could could come up with a cast iron theory on the relationship between these three landmark characters of gaming, simply too many permutations of their story exist to incorporate them all.

Which leaves me with just one question. (Okay, maybe a couple.) Could Link ever be female? If the Hero of Time is a prophesied legend throughout history then why couldn’t it choose a girl or woman? Could we ever see a Zelda game where Zelda takes the lead? We’ve seen her in a variety of supporting roles but does she have the ability to exceed her expectations and become a warrior, not just a princess? And what about Ganondorf; could he ever be portrayed by Glenn Close?

If only, readers.

Female Link artwork at top of page created by Miyu Motuo.

ShareThis

ShareThis